Vancouver has been called the jewel of the Pacific Northwest. But the largest city in British Columbia, Canada, has a darker side. More than 4,000 intravenous drug users live in its downtown Eastside area, turning alleys around Hastings Street into open-drug markets and shooting galleries.

“This alley has a lot of memories,” says Richard Teague, a former heroin addict, gesturing at the garbage-strewn space as he leads a VOA camera crew around his old haunts.

“When you’re an addict and you wanna get your hit in you, you go to the closest spot. And this is it, this alley right here,” he remembers. “… You wouldn’t wait to try and find a room. You went to the nearest place where you could be kinda out of sight, you know, and do your fix and get your high.”

Amid the hazy camaraderie and desperation in such places, people share drugs, needles, diseases and sometimes death. Vancouver reported the world’s highest HIV infection rate among drug users in the 1990s. Teague was one of them, diagnosed with HIV more than 20 years ago.

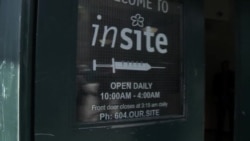

The community responded to the crisis by opening Insite, North America’s first supervised injection facility, in 2003.

Within two years of the facility’s opening, deaths by illicit drug overdose dropped by 35 percent within 500 meters or a third of a mile, researchers from the University of British Columbia and the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS found. Responding to a critique of their work, they later wrote in The Lancet medical journal that "Vancouver's supervised injecting facility had a localized yet significant effect on overdose mortality."

Other research found that, because users there did not share needles, rates of HIV and hepatitis C declined.

Insite’s mission

Andrew Day, manager of Insite’s HIV/AIDS and other harm-reduction programs, explains its mission.

When dealing with people who are addicted and determined to take drugs, “your focus then becomes: ‘If you’re going to use this drug, how can we do it in a way that is safer, reduces the risk of infection, reduces a risk of getting significant wounds, reduces the risk of actually this individual putting demands on other aspects of health care?’ ”

Insite has 12 injection booths, where clients use their own illegal drugs under the supervision of healthcare professionals. Clients get clean needles, pure water and supplies to clean their wounds. The facility, operating near capacity, averages 600 clients a day. Most come for supervised injection, though others come for counseling or other services.

When Teague was using heroin, Insite was his safe haven. Now he visits its peer-counseling sessions to help users get off drugs and deal with HIV.

“I know Insite’s been a godsend for Vancouver, and for a lot of people,” says Teague, who says he’s been off heroin for six years. “Because I know, some weeks at Insite… they probably save 10, 15 people from OD’ing. Because they got nurses on hand, they got professionals that can take care of people like that.”

Supervised injection draws critics

But Insite has its detractors. Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Conservatives in parliament have sought to close the site, which operates through an exemption of federal law so clients avoid drug possession charges.

“There have been multiple studies on these types of institutions … and some suggest that there are public health benefits. Others suggest there are significant health detriments, in terms of increasing rates of addiction,” says David T. Johnson, a former diplomat and a member of the International Narcotics Control Board. He’s also a senior member of the Center for Strategic & International Studies’ Americas program.

Even the healthcare professionals who created Insite initially were skeptical that it would reduce HIV infection, one of its founders says.

“We set ourselves [up] to evaluate whether or not a supervised injection site could help us to control HIV, as well as a whole lot of other issues around injection drug use,” says Julio Montaner, a physician who directs the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS. “And time and time again, the data came in saying yes, it helps, and no, none of the concerns that me, and my colleagues, and the community at large have expressed have materialized.”

Disclosure and discrimination

While HIV infection has been better controlled, Montaner says in a follow-up phone interview, he’s still concerned about the spread of stigma. He contends mandatory disclosure laws like those in Canada and in many U.S. states discriminate by requiring people with HIV to share that information with any prospective sex partner “even if they’re not infectious.”

"HIV exposure has been criminalized" unfairly, Montaner says. When a person with HIV infection has a low viral load and uses a condom during sex, the risk of infection is minimal, he adds. The CDC reports the combination can greatly reduce but not eliminate risk.

Canada is among the top 10 countries in arresting and prosecuting HIV-positive people, the online site Slate reports. It also notes that though the United States has no federal standard, “34 out of 50 states have some law against people with HIV, criminalizing behaviors from nondisclosure to spitting. …”

Teague says he has personally felt the sting of HIV stigma and sees it among some of Canada’s First Nation or indigenous people. “I know a lot of them who feel they can’t go back to the reserve. They feel they’ve been tainted somehow,” he says, adding some have grappled with drugs and prostitution. “… They get HIV, then their elders or parents don’t want them back on the reserve.”

Teague thinks he’s been snubbed for being HIV positive, he says, but he’s upfront about his status “because I’ve been living with it so long.” “When I cleaned up,” the ex-heroin user says, “I learned to be very honest and open.

“I still deal with stigma because of my HIV and I’ve been very open about it. But, best advice that I can give somebody is you have to have a tough skin.”

VOA's Carol Guensburg contributed to this report.