The "wonder drug" pain medications of the mid-1990s have turned out to be a major problem – and a big disappointment.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said not only do they run a high risk of addicting the user, but they can actually make patients' chronic pain worse.

Public awareness of the opioid crisis has grown in the past few weeks, after the sudden death of pop star Prince, who died in April after reportedly seeking treatment for painkiller addiction, as well as with recent legislation passed by the U.S. House on opioid abuse.

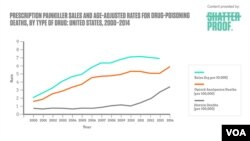

“More than 40 Americans die each day from prescription opioid overdoses,” Tom Frieden, director of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in a statement earlier this month. “Overprescribing opioids -- largely for chronic pain -- is a key driver of America’s drug-overdose epidemic."

A single opioid overdose can also kill, because it can result in respiratory distress. The number of those deaths has been rising to a high of 29,000 in 2014 -- the latest year for which the figures are available.

Of that number, 18,893 deaths were from prescription painkillers. The other 10,574 were from heroin, the opioid of choice when painkillers get too expensive or to difficult to obtain.

In a study in the New England Journal of Medicine in April, Frieden and fellow researcher Debra Houry were blunt: "We know of no other medication routinely used for a nonfatal condition that kills patients so frequently."

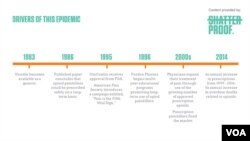

Vicodin, Oxycontin and their cousins, all synthetic versions of the narcotic found in the poppy flower, hit the market in an aggressive marketing rollout in the mid-1990s.

They quickly became popular, providing a euphoric effect while they dulled pain. Studies at the time promised the drugs carried little risk of addiction.

Pain management

The introduction of the new drugs dovetailed with directives by medical experts for health care providers to focus more on pain management.

Doctors began asking their patients to estimate their pain level on a scale of 1 to 10, giving patients more power over what drugs they were prescribed. It wasn't long before the drugs were getting used recreationally.

Thirty-five year-old Nina, now clean, sober, and a successful caterer in Washington, D.C., was a recreational drug user in the 1990s.

"People weren't tracking it like they are today," she said. "So I would 'lose' my prescription or it would 'fall down the sink' or I'd 'leave it behind at Grandma's.' "

Nina said it wasn't euphoria she was trying to achieve with her drug use; it was numbness that she wanted, because her mind was never quiet.

Lou, a 60-year-old travel coordinator, also from Washington, D.C., worked as a pharmaceutical representative in the 1990s, a job that gave her access to drug samples in doctors' medicine cabinets.

"I'd just take them," she said, smuggling home the controlled substances.

She liked to experiment. The results were unpredictable. More than once, she went too far.

'It wasn't my time'

Lou drank an entire small bottle of codeine she stole from a doctor's supply closet.

"I think it was one of the few times I came close to respiratory distress. I just started sweating. My heart started pounding, like crazy pounding. I guess that's what kills people. I just had to lay there and wait for it to pass," she said.

Lou said she was relieved that "it wasn't my time." But she kept using.

A study published in January in the Annals of Internal Medicine found that among 2,848 commercially insured patients who had a nonfatal overdose during long-term opioid therapy between May 2000 and December 2012, 91 percent of them continued to use the opioids. Seventeen percent of those had a second overdose within two years.

Relapse

Lou eventually sought treatment. She got clean and stopped drinking alcohol, as well. That lasted 15 years, until she relapsed.

At the time, her marriage was troubled, her mother had died and there was discord with a sibling. She couldn't sleep.

Her doctor -- who was aware of her addiction troubles -- prescribed Xanax, an anxiety medication that has sedative effects. It, too, is addictive. Lou began chasing her nightly dose with shots of alcohol and got hooked again.

The fact that opioids and other addictive medications are prescribed by doctors can make an addiction harder to recognize, and to treat.

"Some [opioid addicts] actually take their medicines as prescribed, but they have gone to very high doses which impair their functioning. So they're seen as taking legitimate medicines in an honest way," said Dr. Bernadette Solounias, medical director at Ashley Addiction Treatment in Havre de Grace, Maryland.

That appearance of legitimacy, Solounias said, can make it hard for painkiller addicts to recognize a problem, seek treatment, or trust another doctor or addiction counselor.

Solounias said the treatment organization began its "pain recovery" program in 2011.

"We saw that there were people who had chronic pain and who had developed a dependence, sometimes an addiction, to their pain medications. These were medicines that were prescribed for them," she said.

Drug dependency

The drug dependency, for many, was debilitating, but the patients also still had chronic pain to manage.

Solounias said the effects of dependency are reduced function in a person's daily life, including forgetfulness, sedation and preoccupation with having enough of the drug on hand to continue use.

With chronic pain, physical mobility can also be affected. And she said she has found that the CDC's findings are true -- patients dependent on opiates actually have less pain, as well as a better quality of life, when they come off the drugs.

"We're introducing other things -- we may use some non-opiate medicines that help with pain," she said. "Many of them have been inactive. So we get them moving, we strengthen muscles, work with physical therapists, with personal trainers to improve physical fitness. We make acupuncture available to them. Massage is also part of the program."

Patients also get counseling.

Solounias said patients leave the 28-day program with new coping skills.

The CDC issued a new set of guidelines on opioids last month advising doctors to steer away from prescribing the drugs for chronic pain.

Some of its recommendations include urine tests for people being prescribed opioid medications, and short-term prescriptions rather than long-term ones.

New guidelines

The guidelines are geared toward discouraging recreational abuse, as well as addiction. But the new recommendations are already irritating some patients who know they occasionally need to be prescribed opioids to fight acute or post-operative pain.

"Why do I have to suffer because we are protecting a small subset of people?" said Renai, 54, a business analyst in Boston, Masschusetts. She suffers from intense back pain and does not use opioids regularly, but reacted strongly last week when she got a notice from her doctor regarding the new regulations.

Submitting to a urine test was particularly upsetting. "Tons of people take these drugs correctly every day. Why do we treat everyone like a drug addict?" she said.

Even recovering addicts like Nina and Lou find they occasionally need prescription help, although for them it causes a very different kind of anxiety.

Lou recently had both knees replaced, one at a time. She notified her doctors of her addiction history, got support from her recovery community, and took the medications as prescribed.

She said, "It's funny, because I really didn't feel that giddiness this time." Her theory is: when one is actually in enough pain to need them, the euphoria just doesn't happen.

'Here to help you'

Nina has gone through three sinus operations while in recovery from her addiction. She said she, too, needed the painkillers, but felt flashbacks of shame when she had to take several pills, all prescribed, for a few days after the surgeries.

"I finally had to change my thinking," she said. "OK, each of these pills has a purpose. And they're not here to hurt you, they're here to help you."

She said she took each one separately and thought about its purpose as she swallowed.