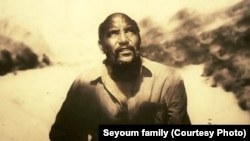

Eritrean journalist Seyoum Tsehaye has been missing for 15 years. Human Rights Watch would like to see that he is not forgotten.

As part of its Free Them campaign to highlight political prisoners around the globe, the rights group is focusing attention on Seyoum, the former head of Eritrean state television, who was taken from his Asmara home by government agents on September 21, 2001, and has not been seen or heard from since.

Seyoum was part of a group of Eritrean journalists rounded up in a crackdown on independent media. Using the hashtag #FreeThem, Human Rights Watch is encouraging people to share Seyoum's story, hold events and tweet to world leaders asking for his release.

Seyoum's advocates believe he is still alive, based on a comment that Eritrean Foreign Minister Osman Saleh made to Radio France Internationale in June.

"The political prisoners are all alive and in good hands," he said.

"Good hands" might be an inaccurate term. A former prison guard who escaped Eritrea in 2010 said Seyoum's hands were bound 24 hours a day. The guard also said that the journalist was being held at the maximum security prison north of Asmara.

The Eritrean government has never commented on Seyoum's arrest or disclosed his location or condition. His family and friends have not had access to him since he was taken away.

Niece seeks uncle's release

Seyoum's 19-year-old niece Vanessa Berhe has been campaigning for her uncle's release for years. She started a website, onedayseyoum.com, to raise awareness of his plight.

She led a silent protest September 23 in London in which people wore black bandanas over their mouths and marched silently to the Eritrean embassy. Berhe said she hopes the attention will pressure Eritrean leaders to at least offer a trial for the jailed journalists and political dissidents.

"The main purpose was to stand in solidarity and in that action also to stand in protest. So our act of solidarity was also an act of protest," she told VOA. "What we're calling for and what we've been calling for since day one is to give these people a fair trial. I mean we think they should be released, but if there is any doubt of their innocence, give them due justice and a trial."

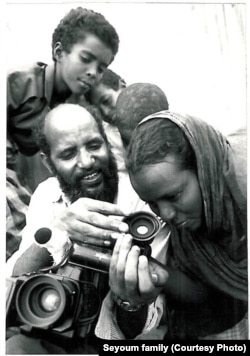

Seyoum, 66, was a famed war photographer during Eritrea's 30-year struggle for independence. He later held various positions including head of the state-run television station Eri-TV.

Between 1998 and 2000, during Eritrea's war with Ethiopia, Seyoum was critical of the government's secrecy and increasing restrictions on free speech and democracy. He apparently made enemies.

The state-run television continues to use his photographs during their broadcasts.

"If they use his materials on television fairly regularly, or frequently anyway, why don't they release him?" asks Andrew Stroehlein, European media director for Human Rights Watch.

Family still hopeful

Berhe said her family hasn't given up hope of seeing him again and believes the campaign will draw the attention of more people.

"He believed in the power of the word, the power of the people and the power of democracy, and I want to show him that what he believed in was strong enough to get him released," she said.

Seyoum's wife and two daughters now live in France. The older daughter, Abie, was two years old when the government arrested her father, and his wife was seven months’ pregnant with their youngest daughter, Beilula.

"The youngest one doesn't have any memories because she never met him. It's very tough for her," Berhe said. "The fact that she doesn't even have any memories and no connection with him whatsoever and that it is impossible to get it because he is imprisoned is something that she's been carrying with her for a very long time."

Human Rights Watch said it plans to continue the Free Them campaign, addressing a different case each week. Unfortunately, Stroehlein said, there is no danger that the rights group will run out of cases.

"We can literally do one political prisoner every hour, and we still wouldn't scratch the surface of a number of people that we're talking about around the world," Stroehlein said. "We're looking at a lot of regimes that are actually getting worse and worse, that are jailing civil society and activists, opposition figures more and more.”

"There's a huge number and so you know it's not fair to take one person over the others,” he added, “but if one person is a symbol for the others, it might be able to put a face on this kind of persecution."