Side stepping with spins on the stage, Indonesian Defense Minister Prabowo Subianto looks his age of 72 as he dances, but the presidential candidate’s social media posts have helped endear him to Indonesia’s young voters. "He seems so friendly," said 19-year-old Putri Ayu Ramadianti on her way to a Prabowo campaign event.

It’s quite a turnaround for the former three-star army general who once led Indonesia’s special forces and is accused of committing atrocity crimes. With Indonesia’s presidential election just days away, he’s the front-runner.

Analysts point to several reasons, in particular naming as his vice presidential running mate the 36-year-old son of Indonesia’s popular president, Joko Widodo, along with social media posts that have gone viral showing Prabowo dancing at campaign rallies.

"In the past he was viewed as a militaristic person, a strongman, but now he’s presenting himself as a chubby old grandpa and this attracts [much] support from [young] Indonesian people," said Yoes Kenawas, a research fellow at Atma Jaya Catholic University in Jakarta.

"When Prabowo named Gibran Rakabuming Raka, the current president’s son, as his running mate, his support from young people really shot up." Widodo must step down as president after his second term ends due to a constitutional term limit.

Approximately half of Indonesia’s eligible voters are younger than 40, and about a third are younger than 30. Thousands of them poured into a convention hall to hear Prabowo speak at a recent campaign event aimed at young voters.

"This world belongs to the you, belongs to the youth," Prabowo said during a speech that provided little in the way of policy details. But while Prabowo hopes to be Indonesia’s president in the near future, human rights activists are trying to derail him by informing the public about his past.

Across the street from Indonesia’s presidential palace, dozens of demonstrators recently shouted, "long live the victims, never be silent," referring to Indonesia’s dark history when the country was led by the dictator Suharto, who was Prabowo’s father-in-law.

But after Suharto’s regime fell in 1998, then-Lieutenant General Prabowo was dismissed from the army for allegedly ordering the kidnapping of pro-democracy activists, of which more than a dozen remain missing and are feared dead. He was also accused of atrocity crimes when hundreds of civilians were killed in East Timor. Prabowo denies all the allegations of wrongdoing.

VOA reached out to Prabowo’s campaign multiple times for comment on the past accusations of human rights violations but received no response.

"I believe that it’s not proper that an activist abductor and a major human rights violator can run for president," said Petrus Hariyanto. Hariyanto was friends with Wiji Thukul, a fellow activist who has not been seen since 1998, a time when many anti-Suharto activists were abducted by government forces.

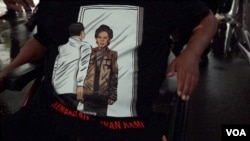

At the demonstration, Hariyanto wore a black T-shirt with a print showing Prabowo looking into a mirror and Thukul’s image staring back at him. Words at the bottom of the shirt translate to "Bring back our friend."

Joining him at the rally was Stephanie Iskandar, a 21-year-old political science student at the University of Indonesia who held a sign that read "fight oppression."

"I have to say I’m really scared that Prabowo is going to be elected," said Iskandar, adding that many young Indonesians know little about the country’s dark past and have been heavily influenced by the Prabowo campaign’s social media posts. "They become very vulnerable with all of this political communication with the young way and with the TikTok and other social media."

At the Prabowo campaign rally, 19-year-old Putri Ayu Ramadianti said she has been learning about Prabowo through social media and downplays accusations of human rights violations. "We don’t know who the real perpetrator is, yet Prabowo was accused," she said.

Philips Vermonte, dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Indonesian International Islamic University, said that Prabowo has been working to clean up his image for years and that issues from the past carry little weight with many of the country’s millennials and Gen Z voters.

"They are very young, and that means in 1998 they were in kindergarten or elementary school, so they do not have or share the collective memories of the authoritarian government for 32 years of Suharto and probably the memories of 1998 reform period when the authoritarian government fell," said Vermonte. "As a result, this issue of human rights violations — do not really resonate with the majority of the voters."