An American team of academics is racing to preserve millions of Cuban historical documents before they are lost to the elements and poor storage conditions.

Many of the documents shed light on the slave trade, an integral part of Cuba's colonial history that was intertwined with that of the United States.

David Lafevor, a history professor at the University of Texas at Arlington, and his brother Matthew, a geography professor at the University of Alabama, have worked since 2005 to make computer copies of millions of documents mouldering in damp storage spaces on the island.

Their latest project is a partnership between the British Library Foundation and Vanderbilt University to capture almost 2 million documents in digital form, a treasure trove stretching back to the mid-16th century of documents about early island life and the slave trade.

David Lafevor said there is nothing like Cuba's documentary record in the U.S.

Though no less ruthless when it came to slavery than the Anglos to the north, the Spanish recognized the "personhood" of slaves once they were baptized into the Catholic Church. Their births, marital status, national origin and deaths were all duly recorded in the town records and stored in church archives, leaving a historical record of blacks and their lives far more detailed than that in the U.S.

Churches became the repository of much of this history because of their central role in island life and because church officials were painstaking documentarians who often were the most educated in their communities, David Lafevor said in an interview.

"The documents are not only pertinent to the Catholic Church because the church was often the most substantial building in town, so other documents were kept there as well," he said.

For instance, while digitizing some documents in the town of Colon, a slave trading post in colonial days that is about 175 kilometers (about 110 miles) east of Havana, Lafevor discovered that a nearby town was founded by former American slaves who had fled Spanish-ruled Florida on the mainland.

The town, Ceiba Mocha, was once known as Ceiba Mocha de la Nueva St. Augustine, a reference to the city that was the capital of Spanish Florida in the 18th century. None of the town's residents were aware of its origins.

Cuba's Catholic Church has played a major role in the preservation project, granting access to church archives around the island and assisting in identifying important documents.

Church officials like Deacon Felix Knight of the colonial Santo Espirito Church in Old Havana, tucked away in a warren of narrow lanes in the city's colonial heart, work with the academics to find and preserve old documents.

"These books reflect life, aspects of the sacramental life of blacks, obviously of whites also," Knight said. "The important thing is to preserve as many of them as possible."

It is especially important to preserve the history of the Afro-Cuban community, whose history has not been well documented in Cuba, he added.

Slavery wasn't outlawed in Cuba until 1886, and American slavers had used the island as a transshipment point for African slaves destined for U.S. slave markets in the South.

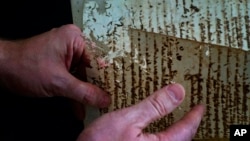

"We are working ... to maintain and recover that which is irreplaceable, a legacy. It's a patrimony, a way of seeing that is very personal," Knight said, holding a book from 1674 that contains records of black births, marriages, deaths and civil status.

The process of digitizing the papers can be painstaking. Each ancient volume is carefully removed from storage and placed on a black cloth used for background. Then each page is slowly opened and photographed. An average book can contain hundreds of pages, all in various conditions of preservation, the writing faded from age and the elements.

The leather-bound volumes are remarkably resistant to decay, considering that many are stored in wooden cabinets in places with little climate control. Knight said churches were built in the colonial era to maximize air flow in the heavy tropical climate. High ceilings and thick walls kept the interiors of the churches cool and dry, helping to preserve the paper and leather-bound records.

Cheaper travel and more choices for accommodations have made the recovery project easier, Lafevor said, referring to a normalization process begun by the Obama administration two years ago. The Tennessee-based team can now fly directly to the island from the U.S., avoiding expensive third-country travel. But even more important, Lafevor said, the growth of "casa particulares," the private homes that rent rooms to visitors, gives them more and cheaper choices for places to stay, allowing them to work for a month at a time.

Lafevor said no one knows how many millions of documents exist in storage, nor how many have been lost to storms, pirate attacks, war and civil unrest, but the project seeks to preserve as many as possible before more are lost to history. He said the current project will run until 2018 and hopes to digitize almost 2 million documents in four cities around the island.

Still, he cautioned, the project is only a small step toward preserving a vibrant historical record, with millions of more documents spanning 500 years left to preserve around the island.