WASHINGTON —

The abduction of more than 200 Nigerian schoolgirls from their boarding school by an Islamic militant group a month ago has created a firestorm on social media.

From Twitter to Tumblr to Facebook to a Change.org online petition with more than 900,000 signatures, millions of people worldwide are voicing their outrage at government inaction and spreading word of the girls’ plight with the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls.

However, this attempt to use social media to raise awareness also has its critics, who say that a hashtag or Facebook campaign oversimplifies the events in Nigeria and rarely produces any tangible results.

Still, it was the lack of awareness and governmental inaction in Nigeria that was the impetus behind #BringBackOurGirls.

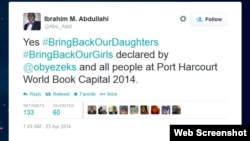

Ibrahim Abdullahi, a lawyer in Abuja, Nigeria, is considered the first to use #BringBackOurGirls – on April 23.

He was at a UNESCO event in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, where Obiageli Ezekwesili, a former World Bank vice president for Africa, used a similar phrase when referring to the Chibok schoolgirls in a speech.

Ezekwesili urged members of the audience to "make a collective demand for our daughters to be released. … We are collectively saying, 'Bring back our daughters.' ''

At that point, Abdullahi said, the Nigerian government had not mentioned the girls or taken any action to rescue them.

So Ezekwesili’s comment stuck with him.

When he was going to tweet the phrase, Abdullahi said he decided to alter it from “daughters” – because everyone may not have a daughter -- to “girls,” because everyone has one girl in their life.

Going viral

Abdullahi, a prolific tweeter with more than 22,000 tweets, said he regularly uses hashtags. But, he said he had no idea #BringBackOurGirls would become as popular as it has.

Abdullahi has about 800 followers on Twitter. His original tweet started going viral when it was retweeted by Ezekwesili, who has about 128,000 followers.

The hashtag’s first big jump on Twitter happened on April 30, with more than 200,000 mentions, according to the social analytics website Topsy.com.

The increased action occurred on a day when Boko Haram claimed responsibility for taking the girls and said it planned to “sell” them.

The hashtag was mentioned more than 400,000 times on May 10 when Michelle Obama used President Barack Obama’s weekly radio broadcast to talk about the Nigerian girls. Just three days earlier, the first lady tweeted a photo of herself with the hashtag.

As of this week, #BringBackOurGirls had appeared nearly 3.1 million times on Twitter, according to Topsy.com.

As news of the girls’ abduction spread in Nigeria, several hashtags emerged, said Miranda Neubauer, a TechPresident reporter who wrote about how the hashtag took hold.

Early versions included #ChibokGirls and #WhereAreOurGirls, Neubauer said, adding that the hashtag “became more simplistic as time went on. ... Eventually this one took off.”

She credited the staying power of #BringBackOurGirls with the general frustration in Nigeria that the government wasn’t doing enough to find the girls and the growing awareness of the story in the U.S. media.

“It does something for awareness when you have Michelle Obama use it,” Neubauer said. “The question remains whether this will lead to the ultimate goal that is to bring the girls back.”

Not everyone agrees that “hashtag activism” is the appropriate way to address what is clearly a complicated issue in Nigeria.

Celebrities, heads of state and even Pope Francis have tweeted support for #BringBackOurGirls.

Unintended results

Some experts, however, say the attention could bring unexpected consequences if pressure for a more robust international response continues to build, John Vandiver wrote in Stars & Stripes.

Already, some hawkish U.S. lawmakers in Congress have used the crisis to attack the Obama administration for being soft on terror in northern Nigeria, raising the specter of a push to intensify U.S. military support in the region, Vandiver wrote.

That sentiment was echoed by Jumoke Balogun, a co-founder and co-editor of compareafrique.com.

“You might not know this, but the United States military loves your hashtags because it gives them legitimacy to encroach and grow their military presence in Africa,” she wrote earlier this month.

Also drawing criticism is that a woman from Los Angeles, Calif., seemingly “hijacked” the hashtag movement earlier this month.

In various media reports, Ramaa Mosely, a filmmaker, said she was moved to action after hearing a mention of the Nigerian girls’ abduction on the radio and began using the hashtag to let people know about the story. ABC News credited her with starting the hashtag.

Mosely was accused on Twitter of hijacking the media campaign and later had to tweet that it was Abdullahi who first used the hashtag.

Twitter hashtags

In the world of Twitter and hashtags, other events have drawn more mentions.

Comedian and Academy Awards host Ellen DeGeneres’ Oscar selfie has been retweeted nearly 3.5 million times.

The top hashtag in 2013 was #bostonstrong, which came into use after the bombings at the Boston Marathon in 2013. It has been used more than 27 million times, according to Twitter.

What makes #BringBackOurGirls unique is that “you don’t usually see something like a social cause, an international social cause, take off,” said Nikki Usher, professor of media at George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs.

“The thing that is interesting is there aren’t usually that many international hashtags that take off that aren’t really specifically related to a large incident of civic unrest, like Arab Spring,” Usher said.

The girls were abducted April 14.

In a 24-hour period ending at noon on Tuesday, #BringBackOurGirls was mentioned 79,037 times on Twitter – nearly once a second.

Abdullahi said he’s pleased that #BringBackOurGirls has gotten the world’s attention and is pressuring the Nigerian government to do more in locating the girls.

Abdullahi said he thinks of the conditions the girls are being held in, an environment they have never been in. When he gets up each day, he said, “I pray for the girls. I pray for their parents. And I pray for country.”

The increased awareness for the missing girls is a positive for the hashtag campaign, but there is also a downside. It’s also bringing international attention to the militant group Boko Haram and its leader, Abubakar Shekau.

"After years of calling out to al-Qaida and taunting world leaders from Barack Obama to United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon, the outcry over the kidnappings has finally put Shekau in the spotlight,” NBC News’ Cassandra Vinograd writes in the Journal Star in Peoria, Ill.

"This is what Shekau always wanted. He's finally gotten placed on the world stage, and this is his time to act," said Jacob Zenn, an African affairs analyst for the Jamestown Foundation, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. He also was quoted in the Journal Star article.

From Twitter to Tumblr to Facebook to a Change.org online petition with more than 900,000 signatures, millions of people worldwide are voicing their outrage at government inaction and spreading word of the girls’ plight with the hashtag #BringBackOurGirls.

However, this attempt to use social media to raise awareness also has its critics, who say that a hashtag or Facebook campaign oversimplifies the events in Nigeria and rarely produces any tangible results.

Still, it was the lack of awareness and governmental inaction in Nigeria that was the impetus behind #BringBackOurGirls.

Ibrahim Abdullahi, a lawyer in Abuja, Nigeria, is considered the first to use #BringBackOurGirls – on April 23.

He was at a UNESCO event in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, where Obiageli Ezekwesili, a former World Bank vice president for Africa, used a similar phrase when referring to the Chibok schoolgirls in a speech.

Ezekwesili urged members of the audience to "make a collective demand for our daughters to be released. … We are collectively saying, 'Bring back our daughters.' ''

At that point, Abdullahi said, the Nigerian government had not mentioned the girls or taken any action to rescue them.

So Ezekwesili’s comment stuck with him.

When he was going to tweet the phrase, Abdullahi said he decided to alter it from “daughters” – because everyone may not have a daughter -- to “girls,” because everyone has one girl in their life.

Going viral

Abdullahi, a prolific tweeter with more than 22,000 tweets, said he regularly uses hashtags. But, he said he had no idea #BringBackOurGirls would become as popular as it has.

Abdullahi has about 800 followers on Twitter. His original tweet started going viral when it was retweeted by Ezekwesili, who has about 128,000 followers.

The hashtag’s first big jump on Twitter happened on April 30, with more than 200,000 mentions, according to the social analytics website Topsy.com.

The increased action occurred on a day when Boko Haram claimed responsibility for taking the girls and said it planned to “sell” them.

The hashtag was mentioned more than 400,000 times on May 10 when Michelle Obama used President Barack Obama’s weekly radio broadcast to talk about the Nigerian girls. Just three days earlier, the first lady tweeted a photo of herself with the hashtag.

As of this week, #BringBackOurGirls had appeared nearly 3.1 million times on Twitter, according to Topsy.com.

As news of the girls’ abduction spread in Nigeria, several hashtags emerged, said Miranda Neubauer, a TechPresident reporter who wrote about how the hashtag took hold.

Early versions included #ChibokGirls and #WhereAreOurGirls, Neubauer said, adding that the hashtag “became more simplistic as time went on. ... Eventually this one took off.”

She credited the staying power of #BringBackOurGirls with the general frustration in Nigeria that the government wasn’t doing enough to find the girls and the growing awareness of the story in the U.S. media.

“It does something for awareness when you have Michelle Obama use it,” Neubauer said. “The question remains whether this will lead to the ultimate goal that is to bring the girls back.”

Not everyone agrees that “hashtag activism” is the appropriate way to address what is clearly a complicated issue in Nigeria.

Celebrities, heads of state and even Pope Francis have tweeted support for #BringBackOurGirls.

Unintended results

Some experts, however, say the attention could bring unexpected consequences if pressure for a more robust international response continues to build, John Vandiver wrote in Stars & Stripes.

Already, some hawkish U.S. lawmakers in Congress have used the crisis to attack the Obama administration for being soft on terror in northern Nigeria, raising the specter of a push to intensify U.S. military support in the region, Vandiver wrote.

That sentiment was echoed by Jumoke Balogun, a co-founder and co-editor of compareafrique.com.

“You might not know this, but the United States military loves your hashtags because it gives them legitimacy to encroach and grow their military presence in Africa,” she wrote earlier this month.

Also drawing criticism is that a woman from Los Angeles, Calif., seemingly “hijacked” the hashtag movement earlier this month.

In various media reports, Ramaa Mosely, a filmmaker, said she was moved to action after hearing a mention of the Nigerian girls’ abduction on the radio and began using the hashtag to let people know about the story. ABC News credited her with starting the hashtag.

Mosely was accused on Twitter of hijacking the media campaign and later had to tweet that it was Abdullahi who first used the hashtag.

Twitter hashtags

In the world of Twitter and hashtags, other events have drawn more mentions.

Comedian and Academy Awards host Ellen DeGeneres’ Oscar selfie has been retweeted nearly 3.5 million times.

The top hashtag in 2013 was #bostonstrong, which came into use after the bombings at the Boston Marathon in 2013. It has been used more than 27 million times, according to Twitter.

What makes #BringBackOurGirls unique is that “you don’t usually see something like a social cause, an international social cause, take off,” said Nikki Usher, professor of media at George Washington University’s School of Media and Public Affairs.

“The thing that is interesting is there aren’t usually that many international hashtags that take off that aren’t really specifically related to a large incident of civic unrest, like Arab Spring,” Usher said.

The girls were abducted April 14.

In a 24-hour period ending at noon on Tuesday, #BringBackOurGirls was mentioned 79,037 times on Twitter – nearly once a second.

Abdullahi said he’s pleased that #BringBackOurGirls has gotten the world’s attention and is pressuring the Nigerian government to do more in locating the girls.

Abdullahi said he thinks of the conditions the girls are being held in, an environment they have never been in. When he gets up each day, he said, “I pray for the girls. I pray for their parents. And I pray for country.”

The increased awareness for the missing girls is a positive for the hashtag campaign, but there is also a downside. It’s also bringing international attention to the militant group Boko Haram and its leader, Abubakar Shekau.

"After years of calling out to al-Qaida and taunting world leaders from Barack Obama to United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon, the outcry over the kidnappings has finally put Shekau in the spotlight,” NBC News’ Cassandra Vinograd writes in the Journal Star in Peoria, Ill.

"This is what Shekau always wanted. He's finally gotten placed on the world stage, and this is his time to act," said Jacob Zenn, an African affairs analyst for the Jamestown Foundation, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank. He also was quoted in the Journal Star article.