In a café in a luxurious shopping mall, Paula Levin places an order for a cup of coffee. It’s an action the young woman now considers a privilege.

“After Leor’s birth, these normal, everyday things just disappeared from my life. I could not function. My life was dominated by the most terrible anxiety,” explains the mother of two sons, Leor (3) and Aryeh (7 months).

Paula, who resides in South Africa’s biggest city, Johannesburg, was enduring a sickness that, even after decades of scientific research, is shrouded in ignorance, denial and stigma – especially in the developing world.

But international research shows that three out of every ten mothers suffer severe depression after the birth of a child. The condition is known as postnatal depression, and it often results in serious health problems – and in extreme cases, even death – for mothers and babies. But, in poor areas of Africa, people have very limited or even no access to the treatment needed to avoid tragedy, and post-natal depression is stigmatized to such an extent that mothers experiencing the illness often ignore it - with tragic consequences.

‘Pain…. And Numbness’

More than 20 years ago, an international expert on postnatal depression, Carol Dix, wrote, “Perhaps the most unfortunate aspect of the problem is that many of the obstetricians, psychiatrists, family doctors and social workers really know little or nothing about this condition that can so devastate a woman’s life, her family’s welfare, and her children’s future. Since it is not supposed to exist, women either deny its presence or suffer alone in shame and guilt.”

Unfortunately, says Debbie Levin, a social worker who’s established a provincial branch of South Africa’s Postnatal Depression Support Association (no relation to Paula), Dix’s words are still true today.

Most mothers get “weepy, anxious and overwhelmed” for a few weeks after giving birth - a condition known as the ‘baby blues,’ says Debbie. Postnatal depression manifests, she adds, when these symptoms become “far worse.”

Paula – who’s written a book about postnatal depression - describes her first birth as “pure panic.”

“I think the birth experience I had with Leor had a lot to do with setting off postnatal depression,” she says. “It was traumatic. I didn’t have much birth support. I should have had a (birth coach).”

Paula’s convinced that the pain she experienced during her first son’s birth, and a subsequent medical procedure to help her give birth, contributed a lot to her depression.

“The pain hit, and I’d never really had any pain before other than a grazed knee or whatever,” she recalls. The pain Paula suffered was accompanied by intense fear.

“It was just scary, it was terrifying. So with each contraction I was just more terrified than the last,” she says. To ease the birth, a doctor gave her an epidural. This is an anesthetic injection into the spinal cord. It deadens feeling in a woman’s abdominal, genital and pelvic areas.

“You kind of dissociate from the experience because you’re not feeling the pain anymore,” Paula says. She’s sure that the epidural procedure was also a factor in her subsequent depression. Because she couldn’t feel her baby being born – “I couldn’t feel one push!” she exclaims - she felt “far removed” from the event and was later “unable to connect” with her son.

On her return home with her baby, Paula says she became “super anxious. I couldn’t sleep, couldn’t stop my thoughts; couldn’t focus on anything; it was just like I was in my head the whole time.”

It took three days before the new mother was able to sleep, but only for a “few minutes.” She took “sleeping pills that could fell a horse” in a desperate attempt to get rest, but the medicine enabled her to sleep for mere two hour stretches.

As her condition worsened, Paula continued to deny there was anything wrong with her. She lost her appetite. Her health suffered. She realized she couldn’t give her baby the care the child deserved.

Guilt, shame and stigma

“I couldn’t feel any joy at having a new baby, I couldn’t feel any joy at all,” Paula remembers.

Debbie Levin says “guilt, self-blame and shame” are characteristic of women who experience postnatal depression.

“They feel that they’ve got a blessing, that the baby was always something that they wanted, and suddenly they’ve got this baby that they always wanted, and they feel incredibly guilty that they’re not enjoying the experience.”

Paula adds, “For me the saddest part of postnatal depression is that my baby was just not the focus. I was the focus – what’s wrong with me, what’s going on with me, why am I not myself; what’s happening?”

Debbie explains that in this maelstrom of emotions, some women feel forced into “drastic behavior. There may be thoughts of hurting herself or the baby, and these women can commit suicide….”

While Paula says she never considered one of these actions, she did ignore her condition for three weeks. “I didn’t believe in depression. I was telling myself, ‘look on the bright side! Pull yourself together!’”

But instead, Paula was being pulled apart.

Debbie Levin says stigmatization of mental illness in society often prevents mothers from acknowledging they’ve got a problem. “The stigma of taking medication, of going to a psychiatrist – all that is associated with mental illness, which women do find very difficult to own up to,” she says.

Debbie says women experiencing postnatal depression often don’t know what’s happening to them; they’re “isolated, alone.”

“Still we find very many women who wear a mask; they pretend that everything’s fine, they go along doing what they’ve always done, pretending that nothing’s happened when inside they may be crumbling, and really, nobody may know about what’s happening to them,” she maintains.

Paula retorts that there’s a “conspiracy of silence” surrounding postnatal depression. “It’s highly stigmatized, and under-reported. When you mention you had postnatal depression, people think you put on a Halloween mask and attacked your baby with an axe!” she exclaims.

But she stresses that women who endure this condition have nothing to be ashamed of. “It is hell enough; you don’t have to make it worse by being ashamed of it. It is an illness, like diabetes,” Paula comments.

After weeks of ignoring her illness, Paula Levin finally sought medical and mental help. A mixture of psychotherapy and antidepressant medication, along with support from her husband and family, set her on the road to recovery.

During her second pregnancy, Paula consulted a birth coach. “I learnt how to focus my mind. I learnt how to manage pain, through focusing on breathing,” she explains.

She didn’t suffer postnatal depression after her second child’s birth.

“Not having postnatal depression this time just made me appreciate every single day. Every day that I could get a night’s sleep, every day that I could smile and enjoy my baby and breastfeed,” Paula enthuses. “And just smelling him, smelling that awesome…. baby smell! All that joy has been magnified this time because I was properly prepared.”

But many other women, says Debbie Levin, and especially those from poorer backgrounds, “never find the path back” to normality.

Family disruption

The social worker explains that certain women are especially vulnerable to postnatal depression. “A woman who finds herself alone, doesn’t have much family around her. Where there’s no support, she feels very alone and can fall into depression.”

A “traumatic birth experience” and “something unexpected” – like the immense pain and the epidural procedure in Paula’s case – often plunges mothers into severe depression, Debbie asserts, and adds, “It can also come from personality factors. For example – women who are perfectionists and very high achievers often get postnatal depression. They find that the baby takes their attention away from their work. Where they were previously very competent in the workplace, they now experience feelings of inadequacy at having to take care of their babies.”

She says one of the “main triggers” is marital problems. “If the mother has been experiencing these, and now suddenly she has the baby, those problems don’t just go away. In fact, they probably get worse.”

Debbie says many marriages break up as a result of postnatal depression. “It affects the whole family. If there are other children, they suffer as well, because the mother’s not going to have the energy to be able to give them the necessary attention. They’re going to start feeling the strain of not having a mother around,” she states.

One of South Africa’s leading experts on postnatal depression, Prof. Linda Richter, has found that maternal mental health is “intricately related” to the child’s physical and mental health. The healthier the mother, the healthier the children – but also the reverse is often true, according to her research.

Richter has found that children of mothers who suffer from the condition often experience behavioral and emotional problems, and are also at risk of “under-nutrition and poor growth,” because their ill mothers weren’t able to nurture and feed them properly.

She says such children may be hyperactive and rebellious – behavior that results in them not attending school. They sometimes find it difficult to form close relationships, and are antisocial.

Richter’s study says, “The prevalence of behavioral and emotional problems is significantly higher among children of depressed mothers as compared to well mothers.

Maternal depression is associated with difficulties in mother-infant interaction, as depression has been shown to interfere with the parents’ capacity to provide adequate responsiveness and stimulation, factors that are critical in supporting early child emotional and cognitive development.”

Richter also associates depression suffered by mothers with an “increased risk of marital conflict and overall disruptive family functioning. These features may account in part for the increased risk of emotional and behavioral problems in their children.”

She says mothers who live in the impoverished areas of Africa are prone to particularly severe postnatal depression…. Yet there’s little recognition of the problem in such areas, and no facilities to treat these women.

"They dump their babies…."

Debbie Levin states that there’s a “complete and dangerous misperception” that postnatal depression is a “luxury condition” that’s only suffered by relatively wealthy women. She says her helpline is receiving increasing numbers of calls from women in poorer urban and rural settings.

“They don’t know where to get help. And the truth is, there aren’t many places that (they) can get help,” she laments.

Debbie maintains that postnatal depression is endemic in the impoverished areas of South Africa, but is “invisible,” with often tragic consequences.

“When you see all these woman putting their babies into dustbins and dumping them in places, that could well be (the result of) postnatal depression. She’s got this baby, she’s poor, she’s got no partner; she can’t cope, so what is she going to do? She’s depressed. She dumps her baby.”

Whereas women who are financially better off are generally able to get the necessary help before it’s too late, says Debbie, poorer women must “go it alone,” often in environments where there’s no acknowledgment of the existence of depression, and “total ignorance” of postnatal depression.

“Probably the more culture-bound a group is, the harder it is for them to admit to it,” Debbie comments. She explains that older, “more tradition-bound” people tend to deny the existence of postnatal depression.

“That is very harmful for the woman who is suffering because then she can’t trust her own sense of how she feels; she can’t get help.”

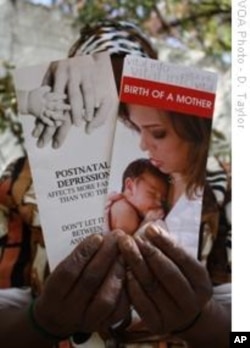

Taking a break from her chores as a domestic worker in Johannesburg, Noxolo Grootboom fingers some pamphlets highlighting postnatal depression. She’s the mother of a son who’s almost a year old, and lives in a tiny house at Diepkloof in Soweto on the outskirts of Johannesburg. Grootboom says the literature is the “first sign” that “this sickness I have is real.”

She says, “After the birth, I felt empty. I am now ashamed to say it, but I did not want the baby anymore. I just always tense. I just wanted to be free of the responsibility of the baby.”

Fortunately, says Grootboom, family members pitched in to assist her, and ensured that she was “well fed” and that her son was well cared for. “No one in Diepkloof knows anything about this illness. They told me I was mad when I told them how bad I felt, and that I did not want the baby,” she says. “I have never seen a doctor about this.”

Both Paula and Debbie Levin emphasize that increased awareness around postnatal depression, and expansion of mental health services to under-resourced areas, is essential if the health of mothers and their children is to be safeguarded.

“When people are better informed about the condition, and that a lot of people experience it, they start to say, ‘maybe I’m not so abnormal after all’ and they often don’t resort to very harmful behavior when they’re armed with knowledge,” Debbie explains.

But at the moment, the social worker says, society in general continues to ignore what she brands “one of the severest threats of all” to maternal and infant well-being.

She adds, “It’s very sad that a completely curable condition still has this hold over society.”

This is part 12 of our 15 part series, A Healthy Start: On the Frontlines of Maternal and Infant Care in Africa