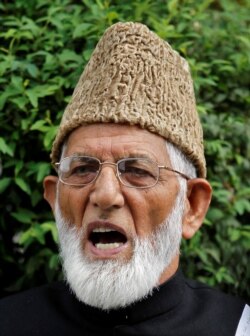

When veteran separatist figure Syed Ali Shah Geelani died last week, the first sign for many in the Kashmir Valley that something had happened was a sudden increase in police and loss of internet and phone service.

With communications suspended and the road to where Geelani was living in Srinagar sealed off, journalists say they struggled to report on his death.

Some saw the restrictions as part of a pattern by India to suppress coverage of events that could trigger protests. Others believed that authorities were trying to curb information that challenged the state narrative.

Fahad Shah, editor of the news magazine The Kashmir Walla, told VOA that internet and phone lines were "snapped" — or suspended — in the middle of the night, leaving no way to communicate. Journalists were told to leave the area where Geelani lived.

Many in the region viewed Geelani as an icon of defiance against India. The region has been the center of tension for decades, with India and Pakistan both claiming it.

Geelani was known for drawing large crowds in the region, and previous false reports of his death had caused disturbances in Kashmir. Journalists and analysts who spoke with VOA say they believe the restrictions were part of efforts by India to block mass participation in his funeral.

Jammu and Kashmir's Home Department, which is responsible for security and other matters in the region, did not respond to VOA's emails requesting comment.

Iconic figure

Geelani started his political career from the town of Sopore, which he represented in the legislative assembly for three terms. But he resigned after militancy erupted in Kashmir in the late 1980s.

He was a founding member of the All Parties Hurriyat Conference, a collective of separatist parties opposed to Delhi's rule in Jammu and Kashmir, and later headed the party Tehreek-e-Hurriyat. But for most of the past 11 years, he had been held under house arrest.

Many Indian officials, as well as some Hindus and Muslims living in Kashmir, believed Geelani worked at the behest of Pakistan. He was known for pushing against any talks with India, favoring instead Kashmir's alignment with Pakistan. But in the 2000s he opposed a solution proposed by Pakistan's then-President Pervez Musharraf.

Geelani's family had wanted him buried in Srinagar's martyrs' graveyard, but the leader's son told the Associated Press that authorities buried him in a local cemetery without his relatives present.

"Nobody from the family was present for his burial," the son, Naseem, told the Associated Press.

"[Geelani's] burial took place in detention," journalist Shah told VOA. "He was detained alive and in death, too, he remained in detention. Now his grave is in detention ... as we witness."

Police issued a statement refuting claims about the circumstances of the burial, as "baseless rumors," the AP reported. The police statement said the claims were made to incite violence, and that police had "facilitated in bringing the dead body from house to graveyard as there were apprehensions of miscreants taking undue advantage."

Obstacles to reporting

On September 2, the morning after Geelani's death, India's Jammu and Kashmir government issued an order suspending telecom services in the region. The orders cited "provocative material on social media" from Pakistan and calls for protests as the reason for cutting services.

Initially in place until September 4, the ban was extended to September 6 by Indian officials. Restrictions were still affecting parts of Srinagar and Budgam districts on Tuesday evening.

For journalists like freelancer Quratulain Rehbar, the lack of internet made it hard to meet deadlines. "I wasn't able to pitch stories on time. I don't know what to say, but restrictions on movement and internet is affecting us like anything. Imagine journalists working in such an environment," Rehbar told VOA.

Aakash Hassan, an independent reporter based in Kashmir, likened the restrictions to the ones that lasted for over 550 days when India revoked Kashmir's autonomous status in August 2019.

"It seems from the kind of restrictions that were put in place, or as happens usually, the authorities are trying to restrict coverage of critical events that it deems [challenging to] the state narrative," Hassan told VOA. "It is clearly aimed at putting a curtain on the ground realities."

But others see the police response as measured for a region that has experienced tensions and clashes.

Manoj Joshi, a fellow at the Delhi-based think tank Observer Research Foundation, told VOA he believes police see cutting communications as a way to prevent people from organizing protests.

"Police cannot be blamed for anticipating trouble. Geelani was a very senior and major leader of the separatist cause. His passing could have been occasion for organizing protests," said Joshi, who writes on terrorism in Kashmir and served on a task force on national security.

Increased security

Some four days after Geelani's death, armed personnel restricted transport. In some places police said a curfew was in place, but in other locations people and vehicles were able to move freely.

Troops were stationed at Geelani's house, with only the leader's relatives allowed in after being verified, journalists said.

"I tried to go near the spot twice. I was brought out from it and kept over 500 meters away," Shah told VOA.

Auqib Javeed, a correspondent for Kashmir Observer, said he quickly rushed to the leader's home when he heard that Geelani had died. But the roads were already sealed.

"The security forces had set up barbed wire and barricades on roads leading to Geelani's house," Javeed told VOA. "Scores of armored vehicles and trucks patrolled main roads in the area. I was stopped at three places and wasn't allowed to proceed despite showing them my Press ID card."

Kashmiri reporter Hassan said that local papers had limited coverage of Geelani's death, "suggesting some form of censorship."

The region's press has previously come under pressure to not cover sensitive issues, including via cuts to government ad revenue or the threat of eviction. Raids and arbitrary arrests are common; police on Wednesday questioned four journalists and raided their homes, the AP reported.

Joshi, of the Observer Research Foundation, said such restrictions are a short-sighted step. "A free press is the best instrument through which a government can keep itself informed about what is happening on the ground," he told VOA.

A political worker from the Jammu & Kashmir National Conference, a regional pro-India political party, who did not wish to be named, told VOA they believe the reaction from authorities suggests India was trying to prevent protests.

Authorities say that the region is more stable since August 2019, but, the political worker said, "If that's indeed the case, why would they deny a decent, respectful burial to a former legislator, which happens to be a fundamental right [for everyone] under Indian Constitution?"

The lack of public funeral "Clearly tells us that the government is aware that there is underlying anger among the people," the party worker said.

Still, political figures in India and Pakistan have expressed condolences, with Kashmir's former chief minister and Peoples Democratic Party chief, Mehbooba Mufti saying, "We may not have agreed on most things, but I respect [Geelani] for his steadfastness and standing for his beliefs."

Pakistan's Prime Minister Imran Khan announced an official mourning period and said that Geelani had struggled "all his life for his people & their right to self-determination."