Last week, an international group reported that more than 20,000 African elephants were poached last year alone.

A day after the report was issued, wildlife officials in Kenya’s Tsavo national park announced that Satao, one of Africa’s largest elephants, had been killed.

The elephant was shot with poison arrows by poachers, who then hacked off its face and stole the tusks.

The carcass was found earlier this month. Conservationists who had followed Satao for years identified the body from the ears and other signs, the French news agency AFP reported.

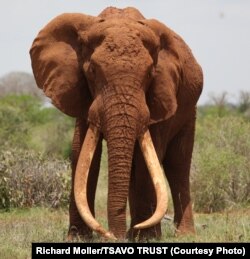

Satao, about 45 years old, was known as a “tusker” – his tusks so long they swept the ground at his feet.

"It is with enormous regret that we confirm there is no doubt that Satao is dead, killed by an ivory poacher's poisoned arrow to feed the seemingly insatiable demand for ivory in far off countries, a great life lost so that someone far away can have a trinket on their mantelpiece," Tsavo Trust said in a statement released late Friday.

Elephant populations endangered

The death of Satao, the latest in a surge of the giant mammals killed by poachers for their ivory, came a day after wildlife regulator CITES warned entire elephant populations are dying out in many African countries due to poaching on a massive scale, the VOA reported.

China is helping to fuel this multibillion-dollar illicit trade with its demand for ivory to use in decorations and in traditional medicines, the AFP reported.

Those eager to reap the benefits - tusks can rake in thousands of dollars a kilo in Asia - include organized crime syndicates and rebel militias looking for ways to fund insurgencies in Africa.

According to CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), 2013 was the third year in a row that more than 20,000 elephants were killed across the African continent.

It said the sharp upward trend in illegal elephant killing observed since the mid-2000s peaked in 2011 and is leveling off.

Satao lived in a vast wilderness stretching over a thousand square kilometers (400 square miles), a major challenge for rangers from the government-run Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) to patrol.

"Understaffed and with inadequate resources given the scale of the challenge, KWS ground units have a massive uphill struggle to protect wildlife," the Tsavo Trust statement added.

Militias behind poaching

Elsewhere, Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo is under constant assault by renegade Congolese soldiers, gunmen from South Sudan and others, the AP reported last week.

The Johannesburg-based African Parks group, which manages Garamba, said since mid April, the 5,000-square kilometer (1,900-square mile) park has faced an onslaught from several bands of poachers who have already killed 68 elephants, about 4 percent of its population.

“The situation is extremely serious,” Garamba park manager Jean-Marc Froment said in a statement. “The park is under attack on all fronts.”

One group of poachers in the park is shooting the elephants from a helicopter and then chopping off their tusks with chain saws, removing the elephants' brains and genitals as well. In some cases, baby elephants that do not yet possess the valuable ivory tusks are killed as well, the AP reported.

African Parks, which runs seven parks in six countries in cooperation with local authorities, said the poachers include renegade elements of the Congolese army, gunmen from South Sudan and members of the Lord's Resistance Army, a militant rebel group whose fugitive leader Joseph Kony is an alleged war criminal, the AP reported.

Social media was humming over the weekend with accounts and photos of Satao's death.

On National Public Radio's website, Mark Deeble, a wildlife filmmaker, wrote of his attempts to film the elephant as it took more than an hour, zig-zagging its way through brush, to approach a watering hole.

"I was mystified at the bull's poor attempt to hide — until it dawned on me that he wasn't trying to hide his body, he was hiding his tusks. At once, I was incredibly impressed, and incredibly sad — impressed that he should have the understanding that his tusks could put him in danger, but so sad at what that meant," Deeble wrote.

Some information for this report provided by AFP and AP.

A day after the report was issued, wildlife officials in Kenya’s Tsavo national park announced that Satao, one of Africa’s largest elephants, had been killed.

The elephant was shot with poison arrows by poachers, who then hacked off its face and stole the tusks.

The carcass was found earlier this month. Conservationists who had followed Satao for years identified the body from the ears and other signs, the French news agency AFP reported.

Satao, about 45 years old, was known as a “tusker” – his tusks so long they swept the ground at his feet.

"It is with enormous regret that we confirm there is no doubt that Satao is dead, killed by an ivory poacher's poisoned arrow to feed the seemingly insatiable demand for ivory in far off countries, a great life lost so that someone far away can have a trinket on their mantelpiece," Tsavo Trust said in a statement released late Friday.

Elephant populations endangered

The death of Satao, the latest in a surge of the giant mammals killed by poachers for their ivory, came a day after wildlife regulator CITES warned entire elephant populations are dying out in many African countries due to poaching on a massive scale, the VOA reported.

China is helping to fuel this multibillion-dollar illicit trade with its demand for ivory to use in decorations and in traditional medicines, the AFP reported.

Those eager to reap the benefits - tusks can rake in thousands of dollars a kilo in Asia - include organized crime syndicates and rebel militias looking for ways to fund insurgencies in Africa.

According to CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora), 2013 was the third year in a row that more than 20,000 elephants were killed across the African continent.

It said the sharp upward trend in illegal elephant killing observed since the mid-2000s peaked in 2011 and is leveling off.

Satao lived in a vast wilderness stretching over a thousand square kilometers (400 square miles), a major challenge for rangers from the government-run Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) to patrol.

"Understaffed and with inadequate resources given the scale of the challenge, KWS ground units have a massive uphill struggle to protect wildlife," the Tsavo Trust statement added.

Militias behind poaching

Elsewhere, Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo is under constant assault by renegade Congolese soldiers, gunmen from South Sudan and others, the AP reported last week.

The Johannesburg-based African Parks group, which manages Garamba, said since mid April, the 5,000-square kilometer (1,900-square mile) park has faced an onslaught from several bands of poachers who have already killed 68 elephants, about 4 percent of its population.

“The situation is extremely serious,” Garamba park manager Jean-Marc Froment said in a statement. “The park is under attack on all fronts.”

One group of poachers in the park is shooting the elephants from a helicopter and then chopping off their tusks with chain saws, removing the elephants' brains and genitals as well. In some cases, baby elephants that do not yet possess the valuable ivory tusks are killed as well, the AP reported.

African Parks, which runs seven parks in six countries in cooperation with local authorities, said the poachers include renegade elements of the Congolese army, gunmen from South Sudan and members of the Lord's Resistance Army, a militant rebel group whose fugitive leader Joseph Kony is an alleged war criminal, the AP reported.

Social media was humming over the weekend with accounts and photos of Satao's death.

On National Public Radio's website, Mark Deeble, a wildlife filmmaker, wrote of his attempts to film the elephant as it took more than an hour, zig-zagging its way through brush, to approach a watering hole.

"I was mystified at the bull's poor attempt to hide — until it dawned on me that he wasn't trying to hide his body, he was hiding his tusks. At once, I was incredibly impressed, and incredibly sad — impressed that he should have the understanding that his tusks could put him in danger, but so sad at what that meant," Deeble wrote.

Some information for this report provided by AFP and AP.