Six months ago, few Israelis had heard of him. Today, the media calls the former high tech tycoon a “superstar,” and everyone knows about Naftali Bennett, leader of the Bayit Yehudi (“Israel Home”) Party.”

As Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu faces criticism from left and right, Bennett’s popularity is rising by the day. The latest polls suggest that if an election were held this week, Bayit Yehudi would triple its seats in the Knesset to become Israel’s third largest party. In fact, Bennett is gaining supporters who don’t even agree with his ultra-religious/nationalist platform, a fact that is greatly troubling Netanyahu’s Likud.

Election basics

Under Israel’s parliamentary system, citizens cast their ballots for a party, not a candidate. The 120 Knesset seats are assigned according to the percentage of the total national votes each party wins. In order to win a seat in the Knesset, a party must win a minimum of 1.5 percent of the total votes.

Usually, the leader of the party with the most seats is named prime minister and tasked with forming a new government consisting of 61 seats. Because no party has ever won enough seats to form a government by itself, parties form coalitions to meet the 61-seat majority. New elections can be called if the prime minister cannot form a government, if a coalition collapses or it is not able to pass its budget.

Last October, Netanyahu called for early elections, saying his coalition would not be able to pass a “responsible” austerity budget. Soon afterward, he announced that Likud would merge with the hardline Yisrael Beitenu Party headed by Avigdor Lieberman. Some believed Netanyahu was looking to gain support for a military strike on Iran’s suspected nuclear facilities. Others believe he wanted to strengthen the party in light of speculation that former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert would run for office and put together a rival coalition.

Either way, Netanyahu’s plans seem to have failed. The latest Haaretz polls show the Likud Party losing as many as a dozen of its present 42 seats in government.

Barak Ravid is a diplomatic correspondent for Israel’s Haaretz newspaper who explains the trend.

“First, a very big part of the Israeli society does not know who they want to vote for,” Ravid said. “This is one trend. The other trend is that you can see very clearly that even right wing voters do not want to vote for Benjamin Netanyahu. They would rather vote for Naftali Bennett’s party.”

Ravid describes Netanyahu’s last four years in office as “more or less” the status quo.

“Nothing really bad has happened, but on the other hand, nothing really good has happened either,” Ravid said. He cites the troubled economy as one factor in Netanyahu’s waning ratings. In addition, he says traditional Likud voters are troubled by the Likud-Beitenu partnership.

“The Likud Party used to be a right-winged but liberal party, and this unification with Lieberman’s semi-fascist party—it’s ultra-nationalistic, anti-rule of law, anti-democracy. This unification may have given Bibi (Netanyahu) the edge in putting together the next coalition, but in the longer term, it caused Likud a lot of damage,” Ravid said.

Finally, Ravid cites the “Pillar of Defense” military operation in Gaza last November. “It’s pretty obvious that Israel did not win this round of fighting,” he said.

New Kid on the Block

So, who is Naftali Bennett and why is he attracting so many voters? Jeremy Saltan manages Bennett’s English-language campaign and believes the attraction is obvious: The political newcomer fits the mold of what people, especially young voters, look up to.

“He is the son of American immigrants who moved to Israel from California,” Saltan said. “He went to national religious schools. He served in elite IDF (Israel Defense Forces) units, including the Sayeret Matkal [special operations force], which is considered by many to be the most elite of all units. Then he left the army and went off to start a high tech company with a bunch of other investors.”

After selling his company for a $145 million profit, Bennett was hired as Netanyahu’s chief of staff, but left after two years because of political differences. He went on to serve as CEO of the Yesha (“Settlers”) Council, where he led the opposition to Netanyahu’s freeze on settlements in occupied Palestinian territories.

A key component of his platform is his opposition to a Palestinian state in the “greater part of the West Bank,” something Netanyahu says he supports.

Saltan explains: “We left Gaza in the disengagement in 2005 and went back to the ’67 borders,” Saltan said. “And of course, since we left, we’ve received two wars of rockets fired against us... and that’s just one of the things that Naftali Bennett does not want to see. He does not want to see us go back to the 1967 lines in Judea and Samaria as well.”

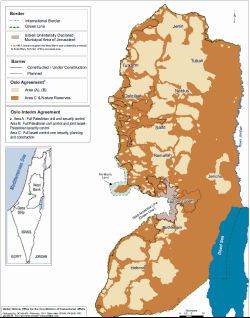

Saltan’s use of the Biblical names for the West Bank is the clue for Bennett’s solution to the Palestinian question, outlined in a short video entitled “The Stability Initiative.” He calls for Israel to annex what is known as “Area C,” or about 60 percent of the West Bank, and grant Israeli citizenship to the area’s Palestinian population, which he estimates is 50,000 (only a third of the United Nations estimate of 150,000).

As for the other areas of the West Bank, “Naftali says pretty simply he doesn’t know,” Saltan said, and further elaborates: “What he’s saying is that the Palestinians’ decision to go to the U.N. with their unilateral [membership] bid, which clearly in terms of a legal standpoint voids the understandings of the Oslo Agreement, means that we are also allowed to go ahead and take a unilateral position,” Saltan said.

While many Israelis worry that such a move could jeopardize Israel’s international standing, Bennett disagrees.

“His response is we annexed the Golan [Heights]. The international community does not recognize it, but we do, and it’s a non-issue. No one’s talking about that now,” Saltan said. “We annexed Jerusalem, and a lot of people don’t recognize that. If we So he says, ‘Why not add Area C to the list of things that the international community does not recognize?”

On other key issues, Bennett would halt the wave of illegal migrants from Africa (“Israel has become an employment bureau for the African continent”); end the exemption of Israel’s ultra-orthodox Jews from military service; end recognition of civil and gay marriages, and deepen the Jewish nature of education and the judiciary.

Strange bedfellows

So, does all this mean that Bennett is poised to defeat Netanyahu? Not this time around, says Haaretz’s Ravid.

“I wouldn’t exaggerate. He’s not Barack Obama of 2008. But he has managed to get to a certain part of Israeli society that felt it doesn’t have anybody to vote for, that doesn’t know who they should vote for and doesn’t see anybody they can relate to.”

Most analysts agree that Netanyahu will stand as Prime Minister. The real question is where he will turn to build his government coalition. On the left, Labor leader Shelly Yachimovich has vowed she won’t join forces with Netanyahu and that could force the prime minister to look further right—even as far as Naftali Bennett—to build his future government.

Meanwhile, Bennett has hinted he could merge with Labor in a post-election coalition. After all, this is Israel, where anything can happen politically and often does.

As Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu faces criticism from left and right, Bennett’s popularity is rising by the day. The latest polls suggest that if an election were held this week, Bayit Yehudi would triple its seats in the Knesset to become Israel’s third largest party. In fact, Bennett is gaining supporters who don’t even agree with his ultra-religious/nationalist platform, a fact that is greatly troubling Netanyahu’s Likud.

Election basics

Under Israel’s parliamentary system, citizens cast their ballots for a party, not a candidate. The 120 Knesset seats are assigned according to the percentage of the total national votes each party wins. In order to win a seat in the Knesset, a party must win a minimum of 1.5 percent of the total votes.

Usually, the leader of the party with the most seats is named prime minister and tasked with forming a new government consisting of 61 seats. Because no party has ever won enough seats to form a government by itself, parties form coalitions to meet the 61-seat majority. New elections can be called if the prime minister cannot form a government, if a coalition collapses or it is not able to pass its budget.

Last October, Netanyahu called for early elections, saying his coalition would not be able to pass a “responsible” austerity budget. Soon afterward, he announced that Likud would merge with the hardline Yisrael Beitenu Party headed by Avigdor Lieberman. Some believed Netanyahu was looking to gain support for a military strike on Iran’s suspected nuclear facilities. Others believe he wanted to strengthen the party in light of speculation that former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert would run for office and put together a rival coalition.

Either way, Netanyahu’s plans seem to have failed. The latest Haaretz polls show the Likud Party losing as many as a dozen of its present 42 seats in government.

Barak Ravid is a diplomatic correspondent for Israel’s Haaretz newspaper who explains the trend.

“First, a very big part of the Israeli society does not know who they want to vote for,” Ravid said. “This is one trend. The other trend is that you can see very clearly that even right wing voters do not want to vote for Benjamin Netanyahu. They would rather vote for Naftali Bennett’s party.”

Ravid describes Netanyahu’s last four years in office as “more or less” the status quo.

“Nothing really bad has happened, but on the other hand, nothing really good has happened either,” Ravid said. He cites the troubled economy as one factor in Netanyahu’s waning ratings. In addition, he says traditional Likud voters are troubled by the Likud-Beitenu partnership.

“The Likud Party used to be a right-winged but liberal party, and this unification with Lieberman’s semi-fascist party—it’s ultra-nationalistic, anti-rule of law, anti-democracy. This unification may have given Bibi (Netanyahu) the edge in putting together the next coalition, but in the longer term, it caused Likud a lot of damage,” Ravid said.

Finally, Ravid cites the “Pillar of Defense” military operation in Gaza last November. “It’s pretty obvious that Israel did not win this round of fighting,” he said.

New Kid on the Block

So, who is Naftali Bennett and why is he attracting so many voters? Jeremy Saltan manages Bennett’s English-language campaign and believes the attraction is obvious: The political newcomer fits the mold of what people, especially young voters, look up to.

“He is the son of American immigrants who moved to Israel from California,” Saltan said. “He went to national religious schools. He served in elite IDF (Israel Defense Forces) units, including the Sayeret Matkal [special operations force], which is considered by many to be the most elite of all units. Then he left the army and went off to start a high tech company with a bunch of other investors.”

After selling his company for a $145 million profit, Bennett was hired as Netanyahu’s chief of staff, but left after two years because of political differences. He went on to serve as CEO of the Yesha (“Settlers”) Council, where he led the opposition to Netanyahu’s freeze on settlements in occupied Palestinian territories.

A key component of his platform is his opposition to a Palestinian state in the “greater part of the West Bank,” something Netanyahu says he supports.

Saltan explains: “We left Gaza in the disengagement in 2005 and went back to the ’67 borders,” Saltan said. “And of course, since we left, we’ve received two wars of rockets fired against us... and that’s just one of the things that Naftali Bennett does not want to see. He does not want to see us go back to the 1967 lines in Judea and Samaria as well.”

Saltan’s use of the Biblical names for the West Bank is the clue for Bennett’s solution to the Palestinian question, outlined in a short video entitled “The Stability Initiative.” He calls for Israel to annex what is known as “Area C,” or about 60 percent of the West Bank, and grant Israeli citizenship to the area’s Palestinian population, which he estimates is 50,000 (only a third of the United Nations estimate of 150,000).

As for the other areas of the West Bank, “Naftali says pretty simply he doesn’t know,” Saltan said, and further elaborates: “What he’s saying is that the Palestinians’ decision to go to the U.N. with their unilateral [membership] bid, which clearly in terms of a legal standpoint voids the understandings of the Oslo Agreement, means that we are also allowed to go ahead and take a unilateral position,” Saltan said.

While many Israelis worry that such a move could jeopardize Israel’s international standing, Bennett disagrees.

“His response is we annexed the Golan [Heights]. The international community does not recognize it, but we do, and it’s a non-issue. No one’s talking about that now,” Saltan said. “We annexed Jerusalem, and a lot of people don’t recognize that. If we So he says, ‘Why not add Area C to the list of things that the international community does not recognize?”

On other key issues, Bennett would halt the wave of illegal migrants from Africa (“Israel has become an employment bureau for the African continent”); end the exemption of Israel’s ultra-orthodox Jews from military service; end recognition of civil and gay marriages, and deepen the Jewish nature of education and the judiciary.

Strange bedfellows

So, does all this mean that Bennett is poised to defeat Netanyahu? Not this time around, says Haaretz’s Ravid.

“I wouldn’t exaggerate. He’s not Barack Obama of 2008. But he has managed to get to a certain part of Israeli society that felt it doesn’t have anybody to vote for, that doesn’t know who they should vote for and doesn’t see anybody they can relate to.”

Most analysts agree that Netanyahu will stand as Prime Minister. The real question is where he will turn to build his government coalition. On the left, Labor leader Shelly Yachimovich has vowed she won’t join forces with Netanyahu and that could force the prime minister to look further right—even as far as Naftali Bennett—to build his future government.

Meanwhile, Bennett has hinted he could merge with Labor in a post-election coalition. After all, this is Israel, where anything can happen politically and often does.