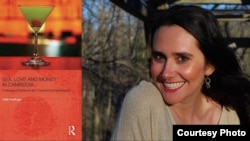

[Editor’s note: A new book from a US professor looks at the world of “professional girlfriends,” Cambodian women who have gift-based relationships with foreign men. In her book “Sex, Love, and Money in Cambodia: Professional Girlfriends and Transactional Relationships,” Professor Heidi Hoefinger, who teaches in the Science Department of Berkeley College, in New York, looks at the intimate lives of Cambodian women and the idea of “transactional relationships.” Women are often praised for these relationships, which bring in money to support their families, but also stigmatized for breaking social codes. In an interview with VOA Khmer Hoefinger said the women are often seeking respect and recognition for their choices, something they don’t always get.]

What motivated you to write this book?

The first time I went to Cambodia was back in 2003. I was just a backpacker who had just finished teaching in India and wanted to tour Southeast Asia among many peers around my age during that time. It was at that point that I first entered one of the hostess bars in Cambodia and became friends with a lot of female bar workers there. We could identify over a lot of things like music, dance, pop culture, and boyfriends. I was drawn to the stories of their lives, and the frenetic energy of Phnom Penh. At that time I decided that I wanted to come back and research and spend time talking to the women that were basically at the heart of it all. I have been going back and forth to Cambodia since 2003.

What is the book about?

The book is ultimately about the strengths and resiliency and challenges of female bar workers in Cambodia, who are employed in the Western-oriented hosted bar sector, which is one sector within the larger entertainment industry. I write about how, amidst a sea of gender constraints—which include strict moral and social codes, sexual violence, corruption, domestic abuse—young women are using the tools around them, which in this case are sex and intimacy, to form relationships with foreign men as a means to improve their lives, make socioeconomic advancements, and ultimately find enjoyment in their lives. The book also sheds light on the relationships themselves that develop between Cambodian women and foreign men, which are multi-layered and complex, but often stigmatized as only ever commercial or only ever exploitative. After spending over 10 years talking to people, I found that often this is not the case, and that people are genuinely seeking true love and intimacy, and that intimacy and economics mingle in complex ways, as they do in any relationship, in Cambodia and beyond. Ultimately, I am trying to humanize and destigmatize the women themselves and the relationships that develop with their Western partners.

How do female bar workers you talked to justify their actions in seeking intimacy with Westerners, either for love or socioeconomic gain?

Most of the women I spoke to at the bars migrate to the cities from the countryside, where their options are very limited, especially with gender disparities in education and society in general. Not many of these women have an education beyond the sixth grade. But they do feel a tremendous obligation to support and contribute to their family, as well. So a lot of them make the decision, a brave decision, to leave the countryside and leave the security of living with their families to move to the cities to seek out labor. So there is a feminization of labor migration in Cambodia.

The problem is when they get to the city, their options are very limited, as well. They can either work in a garment factory for low wages and with very long hours and poor working conditions. They can work in a home, doing domestic work, cleaning and caring for large families. Or they can do street trade, trading food or selling fruit, or have small size businesses that are street-based.

A lot of women have tried all of those options and ended up in the bar because they find them the most lucrative. They have more freedom, in terms of their working hours. The bars are often the places where they can work for a little while, and then quit, and then either raise children or go back to work. So there is a sense of security in those bars, especially when they have good working relationships with the owners and managers.

But doing this kind of work, and even the act of leaving their homes, goes against a lot of the gender codes that are laid out, in particular the Chbap Srey, the Women’s Code of Conduct, which was written historically. Although the codes are not really recited and memorized in the same way they had been in the past, their values are still passed on and reinforced. Even to leave one’s home is a challenge to the Women’s Code of Conduct. In many ways, the women defy the Chbap Srey and the gender code for women in every aspect because they are working late at night, they are working in the environment where people are drinking alcohol and consuming drugs, and of course, they are having premarital sex and relationships. So they are absolutely defying the social code for women in many ways.

However, I found that if they can earn enough capital and provide support to their family and buy homes for their family, which many of them do from their remittances, and pay for their siblings’ school tuition—sometimes they can salvage their tarnished images. In the book, I talk about how they experience this double value system, where they are heavily stigmatized as “broken women” and as “criminal,” but at the same time are highly praised in their family if they can contribute to their family’s economic wellbeing. So it’s complex terrain for the women to negotiate.

By writing this book about gender and money in Cambodia, what have you learned about the country, especially the issues of your interest?

When I first went to Cambodia as a naïve backpacker and eventually a graduate student, I had a lot of my own naïve assumptions, preconceptions, and biases. I assumed that a lot of women that I met at the bars were negotiable for a particular price, and that they were controlled by bosses and managers, and that they have very little decision-making power, and that they were trapped in the bars—which is very powerful discourse that circulates in Cambodia and beyond, especially when you talk about female bar workers. I assumed that every inter-ethnic couple, Cambodian women and their western partners, were all commercially-based. So I had to confront all of my own biases and preconceptions quite quickly when I started to get to know the women and spend time with them in the bars, in their homes with their familes, helping them care for their children, and by doing in-depth intimate ethnographic research. It was through that that I realized most of my assumptions were wrong, and that women themselves were making clear decisions to do this work among limited options.

There were definitely active decisions being made to participate in this work and in this lifestyle. Most of the women were not controlled heavily by bosses and managers. They could make their own choices as to whether or not they would go with clients and what they would or would not do with clients. One of the main findings of the book was that most of them were not doing the kind of pre-negotiated sex-for-cash transaction that we often understand to be commercial sex work. It was more ambiguous than that. It was based in a grey area where sex, love and money were all coming together, but it wasn’t framed as commercial sex work – the women didn’t view themselves as sex workers, and the men didn’t view themselves as clients.

They framed each other as real boyfriend and girlfriend. Yes, of course, there were material expectations. The women understood and knew that these foreigners had more economic capital and social capital than they had. And the women themselves wanted to capitalize on that. So that was an important finding. All of the relationships really made me reflect on the relationships of my peers and friends outside Cambodia, and how all of us have relationships that mingle intimacy, economics and pragmatic reality, and that we should really stop thinking about how “our sex” here is fundamentally different from sex and relationship in Cambodia, or between Cambodian women and their foreign partners. Clearly, there are differences in class and nationality, and access to resources that the couples have to negotiate. But I really try to normalize these stigmatized relationships that develop, and the choices the women make.

How do you feel about Cambodian women seeking socioeconomic empowerment by becoming bar workers, girlfriends to foreigners, or sex workers?

What I am trying to do is destigmatize their choices. Often what happens in Cambodia is this very powerful discourse that these women are either social deviants who are breaking all the social codes, or they are victims that are in need of rescue. The work that they do in the bars is often conflated with trafficking, and it’s assumed they are exploited victims that have not made a decision to do this, and that they are exploited by Western patriarchy. These are the narratives that circulate among a very powerful abolitionist lobby in Cambodia that wants to put an end to all forms of sex and entertainment work as a means of addressing trafficking issues, which is, to me, problematic.

But the sex and entertainment workers themselves – many of whom, but not all –are involved in a sex worker union in Cambodia that has about 6,000 members, called the Women’s Network for Unity. There, they are mobilizing, and demanding rights and recognition for the choices they make. Their argument is: “We don’t want to be rescued by people who think they necessarily know better than us.” What happens when they are “rescued,” is that often, they are often put into these rehabilitation programs or vocational shelters where they are taught to learn to sew and handle a sewing machine, and then placed back in a garment factory. This is not the socioeconomic decision they are making. It’s one that is being forced upon them by people who believe this is a more dignified form of work. What the sex and entertainment workers are demanding is respect for the decisions they make under very constrained circumstances. Bar work is a viable means of labor and employment for some of them—that they choose—andwhat they are calling for is recognition and respect for those decisions, made within the environments that they are in and among the limited options that they have.