Phnom Penh — The European Union Commission on Wednesday is expected to announce its decision on whether to suspend the “Everything But Arms” (EBA) trade privileges, a crucial mechanism that supports Cambodian exports of garments, footwear and rice and has aided in the country’s economic growth.

Speculation has been rife in Phnom Penh over the outcome of the year-long investigation, initiated by the EU Commission last February, with government officials, analysts, economists and average Cambodians all chiming in on the effects of a potential suspension.

A document on the European Parliament website, authored by Italian MEP Danilo Oscar Lancini, proposing amendments to conclusions of the EU-Vietnam Free Trade Agreement, may have accidentally revealed the Commission’s decision – a partial suspension of the EBA for “some products.”

“[A]fter considering the results obtained during an investigation period, the Commission decided, through a delegated act, to withdraw Cambodia’s EBA status on some products,” reads a section of proposed Amendment 6.

The document was likely not for public use yet because while it had been published on the website on February 5, it had not been indexed and could not be searched for on the EU Parliament website.

The EU Parliament and MEP Lancini have not responded to multiple requests for comment on the potential mistake and the Commission has distanced itself for the document. A spokesperson for the EU Commission did say that the process did involve consultations with the EU Parliament and EU Member States.

The content of the document also helps, potentially, clarify a vague admission by Finance Ministry official Vongsey Vissoth, who last week said that the garment sector would see a $500 million dip in exports and pegged potential job losses at 35,000.

As the debate continues over the EU’s decision, there has been non-stop media coverage, both domestically and internationally, of the year-long assessment by the economic bloc, highlighting the high stakes for all involved parties.

The EU’s decision to invoke the investigation into Cambodia’s EBA access was necessitated, the bloc said, by the sweeping political crackdown in 2017 by Prime Minister Hun Sen’s government. This resulted in the Cambodian People’s Party winning all parliamentary seats in the 2018 National Assembly elections, after having already established absolute control of the Senate.

The fallout of any EBA decision will most immediately be seen in the government’s handling of former Cambodia National Rescue Party president Kem Sokha’s treason trial and the continued persecution of the party’s supporters and activists.

In an unusual move, the Phnom Penh Municipal Court has said that the treason trial could last up to three months, taking it well past the February 12 deadline for the EBA decision and potentially allowing for some strategic maneuvering from the Cambodian government based on the EU Commission’s conclusions.

Speaking to VOA Khmer last week, Kem Sokha attempted to separate his trial from the EBA decision, but did admit that an acquittal would go some way to alleviating the concerns raised by the international community.

The EU has continued to push Phnom Penh to reverse its actions on the disbanding of the CNRP, the banning of 118 of its senior members in 2017, and the arrest of Kem Sokha over alleged treason charges. The bloc has also called for reinstatement of the CNRP and its elected local officials.

All it has in return from the Cambodian government, at least publicly, is defiance. The government has maintained that fulfilling the EU’s demands would put at risk the country’s “sovereignty.”

The government did, in what was a potentially conciliatory move, release around 80 opposition activists and supporters on bail, after it had arrested them for allegedly aiding in opposition leader Sam Rainsy’s attempted return to Cambodia in November.

However, Prime Minister Hun Sen last year, on a couple of occasions, linked the fate of the opposition to the EBA outcome, saying removal of trade privilege would be tantamount to “killing” the opposition in Cambodia.

“And I would like to point out that if you sanction me [further], it equally means that [you] beat the opposition in Cambodia to death. I tell you this clearly,” Hun Sen was reported to have said in January last year by the Phnom Penh Post.

Astrid Norén-Nilsson, associate senior lecturer at Sweden’s Lund University, said the suspension of trade privileges would in effect release the Cambodian prime minister from having to listen to Brussels’ admonitions.

“The moment the EBA is suspended or withdrawn, the EU loses any leverage over the Cambodian government,” Astrid Norén-Nilsson said in an email.

She pointed out that it was still unclear if the EU’s decision would definitely seal Kem Sokha’s fate, adding that other domestic factors were at play.

“Any outcome of the trial is still possible after the EBA deadline, including a pardon, to drive the point home that the government follows its own playbook and is not bowing to EU pressure on the opposition.”

Looking at the medium term, the effects of trade privileges revocation would percolate to Cambodia’s critical garment and footwear sectors, and the 750,000 factory workers it employs.

The EBA has been instrumental, in part, in boosting the growth of Cambodia’s garment sector and, more recently, aided in the increase in footwear factories. In 2018 alone, Cambodian exports to the EU reached $5.85 billion, majority of which was clothing and footwear products.

Despite publicly denying any negative impacts to the garment sector, if EBA were suspended, the government has made moves to amend the controversial Trade Union Law, attempted to reduce bureaucratic hindrances to exports and even dropped charges against a few prominent unionists.

But a recent letter from global brands, addressed to Hun Sen, called for wider reforms and actions to ensure trade privileges were maintained. This included further amendments to the Trade Union Law, repeal of an NGO law, commonly called LANGO, and dropping of politically motivated charges against union leaders.

Ulrika Isaksson, spokesperson for Swedish garment manufacturer H&M, even said that “a withdrawal of the EBA privileges will partly lead to a relocation of further investments from H&M Group.”

In a rare rebuttal to the clothing and footwear brands, the Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia released its own statement dismissing the concerns laid out by the brands and called for the EU to instead consider the potential impacts on workers’ livelihoods.

Job losses from a possible EBA suspension would also impact the families of workers, many of whom rely on money sent by garment workers to make ends meet or to repay the mounting burden of microloans in rural Cambodia.

“The potential losses of trade preferences for our sector would by definition reduce employment in our sector for workers,” the Garment Manufacturers Association in Cambodia said in the statement.

Highlighting the importance of retaining the EBA, Casey Barnett, president of CamEd Business School in Phnom Penh, said that Cambodia’s appeal as a low-cost manufacturing destination had diminished on account of recent increases in the minimum wage and pro-labor regulations.

“The real loss in jobs is not with existing jobs – it is with future jobs. Going forward, the absence of trade preferences may deter new investors,” he told VOA Khmer.

If MEP Lancini’s document is an indication of what to expect on Wednesday, the partial suspension of EBA on some products would reflect concerns in Brussels over Cambodia’s near-complete pivot towards China, which the economic bloc would not want to aggravate with a full suspension.

The Financial Times too revealed on Monday that the EU Commission was likely to suspend some of the EBA privileges, according to three anonymous sources.

One of the source said that the economic bloc was staying away from a full suspension, as it was “wary of pushing the [Cambodian] government closer to China.”

“It’s a bit of a nuclear option to take everything away,” one of the people briefed on the decision told the Financial Times. “Everyone knows China would benefit from this in geopolitical terms.”

China in the last few years has become Cambodia’s chief patron and largest source of foreign direct investment. This investment boom was most clearly witnessed in the coastal town of Sihanoukville, where the now-outlawed online gambling operations spurred investments in real estate and tourism.

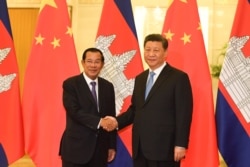

The bonhomie between the two allies was again on display last week, when Chinese President Xi Jinping reportedly told Prime Minister Hun Sen that Cambodia should not “bow down” to the EU’s demands.

Hun Sen, in return, asked that the Chinese government convince its investors to remain in Cambodia, even in the absence of trade preference, and to push more investments and accelerate nascent FTA negotiations.

The potential sanction from the EU could push Cambodia to ever more rely on China, said political analyst Ro Vannak, further changing the regional geopolitical order.

“In case of Cambodia’s falling into China’s grip [as a result of the exclusive reliance], the Association of Southeast Asian Nations would [find it] difficult to speak in one voice, and that could spark a distortion to the regional geopolitical order,” Ro Vannak told VOA Khmer.

Additional reporting by Ananth Baliga and Hul Reaksmey