A U.S. pledge to keep sailing navy vessels through the disputed South China Sea, which Beijing calls its own, could spark a military escalation that may hurt the interests of Southeast Asian states, analysts say.

U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis said on May 29 the United States will continue sending ships near the sea’s contested islands.

China, the dominant military force in the 3.5 million-square-kilometer sea, considers the U.S. maneuvers interference in Chinese waters. Scholars say China has landed a bomber and deployed missiles to islets under its control largely because of the U.S. ship movement.

Five other Asian governments claim all or parts of the sea and bristle at China’s militarization. At the same time, most hope to build trade and investment links with Beijing.

“Currently so far it’s a so-called new normal,” Lin Chong-pin, retired strategic studies professor in Taiwan, said of the U.S. ship movement. For the other Asian governments, he said, “it’s a silent concern but they are very careful what they say.”

More ‘freedom of navigation’ maneuvers

In the latest move, on May 27, U.S. Navy warships sailed near islands occupied by China in the sea’s Paracel Islands that sit east of Vietnam. China normally tracks U.S. ships until they leave. Washington calls those missions “freedom of navigation” operations, or FONOPs for short.

The U.S. Navy has launched seven such operations since President Donald Trump took office last year.

“This will engender an environment of briskly escalating distrust between the militaries of both countries, and that is not good,” said Eduardo Araral, associate professor at the National University of Singapore’s public policy school.

China is building up three reefs in the sea’s Spratly Islands to support missiles and military aircraft, according to an initiative under the American think tank Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The U.S. ship movement has “made provocation against China's sovereignty,” and it “constitute(s) the source of militarization in the South China Sea,” China’s Xinhua News Agency said Saturday.

“For the Chinese it’s a matter of national pride,” said Collin Koh, maritime security research fellow at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. “It’s not just for sovereignty, but if you back down and you allow FONOPs to take place without challenging them, then it will be an affront to the Communist Party. I think the likelihood of China further escalating is not to be further discounted.”

The other South China Sea claimants are Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam. Weaker than China militarily but keen on access to the sea’s natural resources such as oil deposits, they resent China for placing military infrastructure on the tiny islands.

Vietnam and the Philippines vigorously contest some of the islands that China has militarized and were once more outspoken against China.

Both talk to Beijing regularly now one-on-one and through the 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations bloc. China is promoting tourism to Vietnam. In the Philippines, it's rolling out $24 billion in investment and development aid. But anti-China public opinion flares up in both countries when China expands at sea.

“The Philippines will be caught up in the middle of this great power rivalry,” Araral said, referring to China and the United States.

Washington does not have a claim in the South China Sea but regards it as an international waterway. At least one-third of the world’s marine shipping traffic passes through the sea. Trump may be using the ship movement to pressure China over two-way trade and its support for North Korea, some analysts believe.

Competition for loyalty

The United States suggests its South China Sea activity can help the smaller Asian claimants.

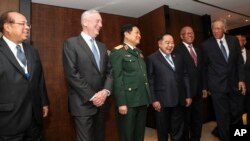

At the Shangri-la Dialogue military leadership forum in Singapore June 2, Mattis and his Vietnamese counterpart agreed that a “strong U.S.-Vietnam defense relationship promotes regional and global security, including in the South China Sea,” the U.S. Department of Defense said on its website.

He and the Philippine defense secretary “emphasized the need” to keep the Indo-Pacific free and open, the website said.

Australia and Japan, which back the U.S. view of an open sea, are expected to send their own ships – though less aggressively than the United States does -- scholars say. Japan, which has its own issues with China, is keen on helping defend Vietnam and the Philippines.

“I think what will happen is the U.S. will carry on with whatever scheduled FONOPs,” said Oh Ei Sun, international studies instructor at Singapore Nanyang University. “There are some other countries, while they wouldn't do like what the U.S. is doing like entering so-called Chinese territorial waters, they would increase their frequency in patrolling South China Sea. We are talking about Japan and let’s say Australia.”