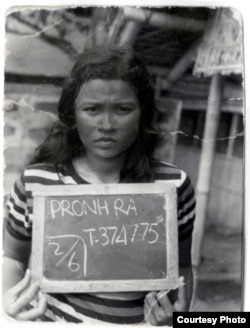

[Editor’s note: The fate of refugees who make it to the United States often goes untold. But Eric Tang, a professor and author, has written a new book on Cambodian refugees in the Bronx, New York, following the life of a former refugee named Ra Pronh to describe what life can be like for a new initiate to the country. In “Unsettled: Cambodian Refugees in the New York City Hyperghetto,” Tang, a professor of African and Diaspora studies at the University of Texas, describes life for the wave of Cambodian refugees who ended up in the Bronx, where he had worked as a community organizer in the early 1990s.”]

What inspired you to write this book?

The origins of this book can be traced to the late 1990s when I was a community organizer in the Bronx working with refugee teenagers. I grew up in New York City. After college, I found my way to the Bronx as a community activist and was asked if I was interested in working with refugee teenagers, most of them from Cambodia, who really didn’t have any program or services or any extra things in their life to support them through a life of poverty, bad housing, and watching their families struggled through welfare. And I said “Sure.” I was a young guy, in my early twenties. Well, after one year of volunteering, I really grew to love the work, and I decided that I was going to do this work full-time. So I began to direct the Youth Leadership Project for Cambodian teenagers in the Bronx. It’s from those experiences that I decided, when I became a professor, to write my first book about this forgotten community of Cambodian refugees in the Bronx.

What is the goal of your first book? How do you think this story can be related to people currently escaping civil wars in their countries?

The book has several goals. The first one being to tell the story that hasn’t been told about a forgotten community in the Bronx of Cambodian refugees who survived the war, the genocide, the camps. What happened to them 25, 30 years after the fact? So the first goal is to leave behind some statement that this community existed, and they survived. In some ways, they resisted what happened to them. The second goal is to have those who believe that once you settle refugees, and that their struggle is over, and the work is done, to think more deeply about that, to think about what it is that refugees continue to need, how they continue to survive in the United States and in other so-called first-world countries after resettlement, to understand that the refugees’ journey does not end with resettlement, and to have policy makers understand that as well. That is another important goal of the book. I don’t think many scholars, writers, or journalists, have done a longitudinal study, at least not in a deep qualitative way, when it comes to refugees.

For those abroad who are living in the country where a large segment of their population fled as refugees, I think this serves as a reminder, a cautionary tale, if you will, that not everything is as one assumes it is [after the refugees resettle]. You know, it’s not like their relatives, their friends [who came to the United Stares] don’t continue to struggle and don’t continue to live as a fugitive in the new homeland. Don’t get me wrong. I am not saying in any way that the poverty in the U.S. is equal to the depth of poverty that people experience in developing countries. I’m not making a one-to-one, apples-to-apples comparison. What I am saying, though, is that there is a new kind of struggle that takes shape here, and there are new ways in which inequality, premature death, and underdevelopment take shape in the U.S. context. It’s important for those who see their family members and relatives go abroad to understand that in the new land there continues to be significant forms of struggle, that things are unclosed, and as my title suggests, “Unsettled.”

You chose the story of a Cambodian woman, Ra Pronh, to tell the story of the immigrant struggle to survive and build a new identity in the new land of America. Why did you choose her and her story?

Ra Pronh is a woman who has experienced the many dimensions of what I call, refugee time, or “refugee temporality” in the United States. She is a woman who can draw a connection between the camp and the ghetto, meaning that she understands clearly the ways in which the refugee camp and her new environment in the U.S. ghetto form an unbroken chain, how they are in many ways similar, and that idea intrigued me, because we’re always taught to believe that the refugees experience some profound transformation upon arriving to the United States, that there is this clean-break between the past and the present.

What I experienced in my conversations with Ra was that she was ambivalent about this notion of resettlement equaling freedom, that there’s a way in which she is still moving, still struggling as a refugee. She didn’t believe that it was possible or necessary to let go of her survival skills in the United States. Instead, she understood that her fugitive struggle was ongoing. I got that impression from her immediately after sitting down for interviews with her, and I decided that this book would best be told—the story of the Bronx Cambodians best be told—through the experience of this one woman from the war through the camps, and into the ghetto.

How was life for the Cambodian refugees in the Bronx in the late 1990s, as best you can tell from Ra’s story?

Ra is a woman who exemplifies many of the struggles that the broader community went through. When they arrived to the Bronx, the first thing they were confronted with was harsh living conditions. Resettlement agencies placed them in whatever apartment units were available. Many of these units had been abandoned by previous tenants, who found them uninhabitable because landlords didn’t take care of them. Some of them were buildings where fires had taken place, and other tenants moved out, fearing that eventually the whole building would burn. Here is where they decided to place the refugees from a war. The resettlement agencies said, , “Oh, look there are a lot of empty units here. You know, we can keep these families together.” But did anyone stop to ask why there were so many empty units? They were empty because no one else wanted them. So the first real struggle was housing, bad housing. The conditions were horrible. There wasn’t heat. There wasn’t hot water. The windows were broken. This is what the refugee survivors had to put up with when they first got to the Bronx.

And then the refugee resettlement agency says, “The first thing you need to do is to find work, find immediate employment because we need to prove that refugees can make it in America.” But many of the refugees were not equipped to take the good jobs that were available, at least the jobs that provided livable wages. So they took poverty wage work. They took work as garment workers, taking materials from the retail middlemen, and assembling garments at home using a sewing machine, and they got paid pennies per piece. When that wasn’t enough to survive on, many of them— in fact, 80 percent of the Bronx Cambodians—applied for welfare, and stayed on welfare for the next decade and a half. Many of them today continue to survive on welfare.

But in 1996, the federal government passed the law that severely restricted how much welfare they could take. There was a huge crisis during the late 1990s and early 2000s as many people were cut off welfare. A lot of families had to find additional poverty-waged work, working in factories or taking on garment work at home. On top of that, the teenagers were dealing with the same issues that many black and Latino teenagers were dealing with: police harassment, police brutality, street violence that was spurred by the drug trade. This was the refugee reality they stepped into during the ’80s and ’90s into the early 2000s.

What do you think the experiences of Cambodian refugees can tell us about the US approach to resettlement of refugees, the successes and failures of its approach?

The United State prides itself on the notion that it is the most generous refugee resettlement country in the world. That’s a very interesting thing to say today, in light of the anti-refugee backlash against Syrians following the terrorist attack in France. But the current rhetoric notwithstanding, our government celebrates itself as the most generous because it claims to resettle the most refugees. But if you think about it, when we look at how the US compares to other countries, which are much smaller and have far less resources … we really don’t resettle that many or as many as other countries do, per capita.

But here is the other thing that the United States does not say when it talks about how generous it is: It doesn’t talk about what happens to the refugees after they resettle here; after they get here, the vast majority subsist in working poverty for generations. This is because we don’t really have a plan, an economic plan, for what happens to them after they arrive. Instead, we live by this notion of work first, immediate employment, because we want to prove again that the US is the land of freedom and opportunity. So we say, “So long as these refugees are working, we’re doing a good job.” But what are these jobs they are getting? They’re sweatshop jobs. They’re jobs in poultry factories where they can be fired immediately, where they’re the last hired, the first fired. They’re working in horrible conditions. They do this work at the expense of developing real human capital: language skills, professional development, things that would allow them to get jobs that pay livable wages, so that they can do better and their children can do better. So instead they’re stuck in the state of working poverty. This is not a sustainable resettlement policy.

The other impact is on the children, because as their parents struggle with poverty, the children too have to start taking on jobs much earlier, working in low-wage retail, fast food, you name it. What we notice in the Bronx is that the second and the third generation are not doing well. In fact, some might argue they are doing just as badly, if not doing worse, than their parents, because they don’t have the same survival skills that their parents have. But they are living in the same impoverished conditions.

In what way do you think the US government can make its resettlement approach a better one as it vows to take a large number of Syrian refugees escaping the civil war?

Whatever I say here, I think, should apply to all people living in poverty in the United States, in the urban United States. But to answer the question, the first step is to reverse this notion that the refugees need to find work immediately. The “work first” immediate employment doctrine is not a smart way of going about refugee resettlement. We should give the refugees more than the six months of aid that we are currently providing them before telling them, “Go find work.”

We should extend that to be at least two years, and during that time, have the resettlement agency work more deliberately to find a better economic match between the skill set of these refugees and the local economy. What’s the point of rushing them to take on sweatshop jobs, simply to say, “Oh, we’ve got an 80 percent employment placement rate, only three months after resettlement.” To me, that doesn’t necessarily sound like good news, especially if these are poverty-waged jobs.

What I think needs to happen is that the federal government needs to extend its resettlement program, the timeline of its resettlement program, which provides funding for refugees to take on job training, to be supported with transitional aid. We need to extend that period, and I say two years just as a ballpark figure, not limited to that particular time limit, but clearly longer than a few months they have now. Then to work with the refugee resettlement agencies to find jobs that are good economic matches with their current skill set, and that allows them to advance in those jobs as they develop new skills over time.