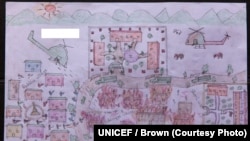

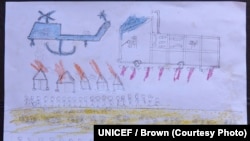

Houses set on fire. Helicopters firing from above. Residents fleeing gunfire and sword-wielding mobs.

Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh have accused Myanmar’s state security forces of numerous rights abuses in the wake of Aug. 25 attacks by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army (ARSA) on police and army posts in northern Rakhine State.

But the horrific scenes described above were not conveyed to journalists or human rights monitors gathering testimony. Children drew them.

“When we’re working with children trying to help them overcome their trauma, one of the ways we do it is to have them draw pictures,” Anthony Lake, the executive director of UNICEF, told reporters in Cox’s Bazar on Tuesday. “And I’ve seen in so many places, happy pictures from children, in places where children were suffering hugely. But nonetheless they could draw happy pictures of their homes or what they’ve seen around them.”

But these were very different.

“The pictures we have seen here are horrifying. They reflect children seeing things that no child should ever see, much less endure,” he said.

Images shown during the briefing and others shared with VOA showed scenes of unimaginable carnage.

In one, men that appear to be soldiers gun down civilians while others – presumably mobs – use long swords to hack away at defenseless victims.

Another shows drowned bodies in the Naf River separating Myanmar and Bangladesh. Dozens of people have died after boats capsized trying to make the journey.

Several show helicopters and army vehicles descending on villages, many of them ablaze.

Lake said he spoke to one boy who said he saw other kids who had been playing football killed.

“Imagine if you were a child, and you saw that, how long would it take you to recover from that, if ever you could,” he said.

Denial of ethnic cleansing

Myanmar’s army, and the civilian government led by de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi, have strenuously denied allegations that its forces are carrying out atrocities against civilians, maintaining they do their utmost to avoid collateral damage and insisting that any violations will be investigated if proper evidence is brought to them. Diplomatic representatives abroad have also refuted allegations of ethnic cleansing.

In a speech late last month Aung San Suu Kyi said military operations stopped after Sept. 5, but new arrivals continue to come into Bangladesh, many of them likely in search of food.

Senior officials from both countries met this week in Bangladesh. Afterwards, Myanmar said it would take back refugees who had fled under a verification process established in the early 1990s. But doubts remain.

Myanmar’s crackdown on ARSA insurgents has sent more than 500,000 Rohingya across the border where they have joined swelling refugee camps, creating what United Nations Secretary General Antonio Guterres has called a “humanitarian and human rights nightmare.”

Some 60 percent of the refugees are children, and half are under the age of five, according to UNICEF. Aid groups worry about meeting their health, nutrition and schooling needs.

Children refugees

The refugee camps are teeming with children, who run up and down hilly settlements and swim in murky river water. Some were seen helping build makeshift shelters. Hundreds of thousands of Rohingya refugees already live in the area.

A spokeswoman for UNICEF told VOA that the drawings they distributed were from several children in the Balukhali camp who come to the group’s makeshift “child-friendly centers.”

UNICEF says staff members were present while some of the drawings were completed.

The children who drew them are from ages 6 to 14, and all were done in the past few weeks.

The allegations that have emerged from Rakhine State, which are similar to claims arising in the aftermath of the first attacks by the ARSA nearly a year ago, have been met with widespread doubt by members of the public in Myanmar, many of whom believe the stories are nothing more than “fake news.”

Several rallies in support of the government have been held in downtown Yangon, while local media organizations have cast international coverage of the crisis as biased and slanted.

Myanmar led a group of diplomats and UN officials to the center of the conflict in northern Rakhine on Monday. The area has been largely closed off to aid groups and outside observers since Aug. 25.

A previous exception to the lack of access occurred last month when the government flew reporters to the area to see mass graves of Hindu residents allegedly killed by ARSA. The group denied the allegations.

One diplomat said in a Tweet during the visit that Maungdaw Township, which is near the border with Bangladesh, looked like a “ghost town.”

![[NAME CHANGED] On Oct. 2, 2017, a drawing by a Rohingya boy, Abdul, revealing the horrific experiences he endured while fleeing from Myanmar to Bangladesh, at the children friendly space at the Balukhali makeshift refugee camp in Cox’s Bazar district in Bangladesh.](https://gdb.voanews.com/8ada84a8-ff13-4821-bcf8-86acd4980b29_cx0_cy4_cw0_w250_r1_s.jpg)