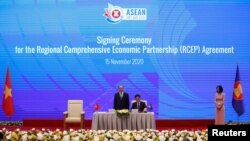

Several leaders from 15 Asia Pacific countries, who signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) on Sunday, have praised what is being regarded as the world’s biggest trade pact.

RCEP members, which include 10 ASEAN members plus China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand, represent 30% of world’s population and 28% of its economy. The purpose of the partnership is to reduce taxes on the trade in goods and remove nontariff barriers.

Japanese trade minister Hiroshi Kajiyama said the deal will create a set of “free and fair economic rules.” Chinese Premier Li Keqiang described the pact as “a ray of light and hope amid the clouds.”

The RCEP is widely regarded as a China-backed alternative to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), which covers 11 countries around the Pacific, but not China.

The agreement is a culmination of “eight years of negotiating with blood, sweat and tears,” Mohamed Azmin Ali, Malaysia’s international trade and industry minister, said.

After years of deep suspicion that China would dominate the trade club, intense squabbling over trade rules, and India dropping out of the negotiations, in the end, the RCEP is a rather simple agreement focused on the trade of goods.

But will the agreement enhance China’s global image at a time when Beijing is engaged in a trade war with the U.S.?

“The RCEP allows China to cast itself as a champion of globalization and multilateral cooperation. It also puts China in a better position to determine the rules governing regional trade,” said Gareth Leather, Senior Asia Economist, at Capital Economics.

Beijing is relieved that the new pact does not commit members to a significant opening up of services, liberalization of government procurement, or rollback of industrial policy, demands imposed on CPTTP members, Leather suggested.

The CPTPP replaced the U.S.-backed Trans-Pacific Partnership after the Trump administration walked out of it. Its members are Australia, Brunei, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore and Vietnam.

The RCEP signing has raised questions about whether it would prompt the United States, under a President Joe Biden, to return to an international trade agreement like the CPTPP instead of remaining isolated.

“Given the massive challenges on the domestic front and preexisting concerns about the unequal benefits of free trade agreements, it's not obvious Biden will choose to join the revised CPTPP,” Matt Ferchen, head of Global China Research at the Berlin based think tank, Merics, told VOA.

“Yet the signing of RCEP will be a further spur to the U.S., and presumably to India, to not be left outside looking in at the largest trade agreements in the Indo-Pacific region,” he added.

Though signed with much fanfare, the RCEP leaves many thorny issues unsolved.

It does not deal with trade disputes among its member countries, such as China and Australia. It focuses on the exchange of goods but does not address trade in the services sector, which is growing faster worldwide than trade in goods.

“It does not address such major trade barriers as IP protection and state subsidies,” said Lester Ross, a partner in an international law firm, WilmerHale.

“It is also unclear whether RCEP will have any impact on coercive trade barriers imposed by a member state against another member state, like China’s recent restrictions on certain categories of goods from Australia,” he said.

Australia’s Trade Minister Simon Birmingham sees the RCEP as an opportunity to open the trade doors that China has shut. The deal puts the ball in China’s court to abide by not only the terms but the spirit of the new trade pact, he said. Australia hopes China will relax restrictions it has imposed on imports of certain Australian goods.

Though RCEP had helped reduce tariffs, smaller countries in the pact, like the 10 ASEAN members, have different reasons to worry. For instance, their dependence on China might increase although it is not clear if China will buy more of their products.

“Laos and Cambodia are already part of the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area, so RCEP won't necessarily imply a major change in trade barriers with China,” Ferchen said. The ASEAN members are Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand, Brunei, Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam.

“Their bigger challenges are being overly dependent both economically and geopolitically on China, especially at a time when U.S.-China strategic competition is rising in Southeast Asia and countries are being asked to choose sides,” he explained.

Chinese state media has seen in this an opportunity to pat the government’s back.

“The RCEP includes multiple U.S. allies; their agreement to the deal is an affirmation that China will remain an intrinsic economic partner for them and that the region will ultimately work and cooperate together,” CGTN, the state-owned broadcaster, said.

It would take some time before any country sees the benefits of the deal because nine of the 15 member nations have to ratify it before it takes effect.

"The economic benefits of the deal might only be marginal for South East Asia, but there are some interesting trade and tariff dynamics to watch for North East Asia," said Nick Marro at the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU).

"Ratification will likely be tricky in national parliaments, owing to both anti-trade and anti-China sentiment," he said.